How to Install Flat-Pack Kitchen Cabinets

Ready-to-assemble cabinets are sturdy, offer a myriad of design and quality options, and cost less than assembled versions.

Synopsis: Ready-to-assemble (RTA) cabinets, also called flat-pack cabinets, have a reputation of being poor quality, but there are sturdy options on the market. And not only do RTA cabinets typically cost half of what assembled cabinets do, the lead time and manpower required to install them is significantly reduced. In this article, builder and remodeler Andrew Steele breaks down a project in which a team of three carpenters assembled and installed a kitchen’s worth of flat-pack kitchen cabinets.

Ready-to-assemble (RTA) cabinets, also called flat-pack cabinets, come as precut, unassembled parts shipped in cardboard boxes like IKEA furniture. They’re often thought of as poor quality, but that doesn’t have to be the case. Like most things, there are different lines of RTA cabinets, and while entry-level offerings are made of particleboard with slab drawer fronts and thermofoil coatings, the ones we use have plywood boxes, solid wood frames, dovetailed drawer boxes, and soft-close hardware. Many people assume that RTA cabinets are always frameless like Ikea cabinets, but I generally use face-frame cabinets for the traditional look that most of my clients prefer.

Start with a plan

Cabinet layout should take advantage of all the available wall space with consideration given to storage needs and the location of nearby appliances. Remember to leave room for filler strips where adjoining cabinets meet at inside corners so drawers and doors can fully open.

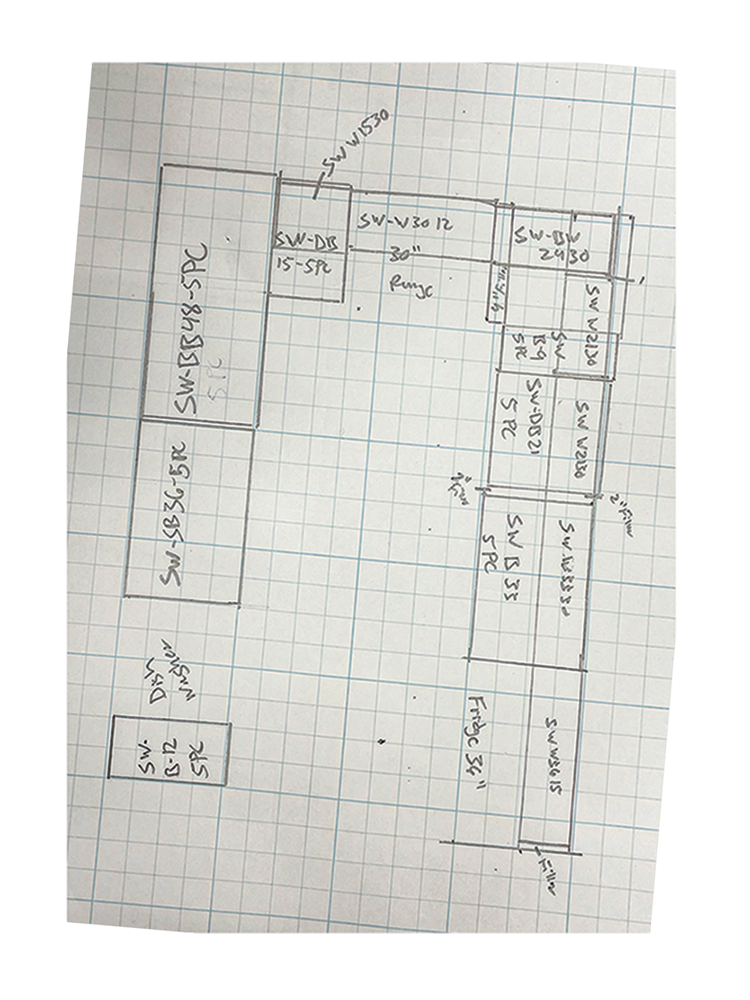

Sketch it out

The cabinet design should be reviewed and agreed upon by the homeowner. A 2D drawing showing cabinet sizes and locations and appliance locations is often enough, but the more detail the better. Have sample cabinets or at least sample doors and drawers to show as part of the design process. These preliminary steps ensure installers and clients agree on the size and finishes of the cabinets to be installed.

Get unpacked

The first step is to unload the cabinets from the delivery truck. The cabinet boxes are heavy and bulky, but smaller than assembled cabinets, making them a good choice for tight spaces and walk-up multifamily buildings, like this mountainside condominium. Navigating this switchback staircase on the condo building would have been more difficult with fully assembled cabinets. Unfortunately, because they have all the same parts and hardware, RTA cabinets weigh the same as their fully assembled counterparts.

Divide and conquer

I like to install upper cabinets first, so I sort the uppers and lowers and move the lowers out of the way. I pick where I’ll start the installation and build those cabinets first. While my team sorts and moves cabinets, I lay out their locations directly on the wall based on the kitchen design. I screw a level 1x ledger to the studs to make setting the uppers easier. The holes will be covered by a tile backsplash.

TIPS for smooth assembly A large, smooth work surface A good table made from a pair of sawhorses and a sheet of BC plywood is critical for box assembly. |

I use RTA cabinets to save my clients money, as they generally cost half as much as similar assembled cabinets, even with the extra time it takes me and my two carpenters to assemble them. The cabinets are also very sturdy because they’re fully glued with wood glue and not hot-melt adhesive like inexpensive assembled cabinets. The cabinet manufacturer I work with in North Carolina also offers an assembly service, but in my experience you almost always end up with at least one damaged cabinet from the shipping process. Fortunately, replacements are fast and painless—but we assemble our RTA cabinets ourselves to reduce damage and minimize lead time.

If I pick up the order two hours away in Raleigh, N.C., I can have a full kitchen’s worth of cabinets in one to two days, which is pretty phenomenal given the supply-chain problems common today. My RTA-cabinet supplier, Kitchen Cabinet Distributors, offers a wide range of sizes starting at 9 in. wide and going up to 42 in. in 3-in. increments. Upper cabinets come in the same widths as the lower cabinets and are available in 30-in., 36-in., and 42-in. heights. There are also 12-in.- and 15-in.-high cabinets meant to go over ranges and refrigerators, as well as pantry cabinets, end and appliance panels, and a wide range of trim pieces and accessories that rival what’s available from a semicustom cabinet manufacturer.

Build and install the uppers

Each upper cabinet box will have a back, two sides, a bottom, a face frame, and doors. I like to dry-fit the back, sides, and bottom to ensure the dadoes and rabbets are cut and sized correctly and I won’t have any issues gluing them together.

1. Glue and screw the back

I apply wood glue to the back and sides and then slip the sides into the rabbets that are on the cabinet back. I turn the cabinet upright and clamp the pieces together with bar clamps. Then I use a 6-in. #2 Phillips bit to drive the screws into the pocket holes that come predrilled in the cabinet back. To avoid stripping them, I start my drill at the lowest torque setting and increase it by a notch or two until it fully tightens the screw without stripping. Then I leave the clutch at that setting.

TIPS for smooth assemblyLots of clamps I use mostly 24-in. F-body bar clamps, and a few 36-in. and 12-in. clamps are handy too. You’ll need at least six clamps to assemble a cabinet. |

2. Fit the top and bottom

I generally leave the clamps on until the glue sets, but 18-ga. brads keep cabinet construction moving if I don’t have time for the glue to set. I only brad-nail when the cabinet side won’t be visible when it’s installed. I then apply glue to the rabbets for the cabinet top and bottom and slide them in, making sure the finished side is inside the cabinet. Once the bottom is in, I clamp the sides or brad-nail through the side of the box into the top and bottom to hold the parts together while the glue dries.

TIPS for smooth assemblyLots of glue I like to use a combination of Titebond II for boxes and Titebond Quick & Thick for gluing on face frames. |

3. Attach the face frame

Before attempting to glue on the face frame, I check the box for square and clamp in the appropriate direction to correct any out-of-square conditions. I use Titebond Quick & Thick fast-setting glue to attach the face frame to the cabinet box, because it sets in about 15 minutes. I also use 1-in., 23-ga. pins to toenail the sides and bottom of the cabinet to the face frame. Pay attention to how the face frame is installed or you may put one on upside down. If you do, it’s easier to drill new pilot holes for the door hinges than it is to remove the frame.

4. Install the wall cabinets

I generally start by centering the cabinet above the range. I like to set the first upper cabinet in place and screw it into a stud at the top, then set the next cabinet in the run and use clamps to clamp the face frames together. Here, I installed the range wall of cabinets and then worked my way around toward the refrigerator. With the range wall of cabinets installed, I could calculate the exact size of the filler strips needed to equally space the remaining cabinets. I use face-frame clamps from Bessy, which align the face-frame fronts and hold them together while I predrill and screw the cabinets together with trim-head screws. I try to hide these screws behind the hinge mounting plate. Once all the cabinets are in place I install the doors so they’ll be out of the way.

Build and install the bases

The base cabinets assemble much like the uppers, except base cabinets generally have drawers and a toe kick. Drawer base cabinets take longer to assemble than standard base cabinets, which you should keep in mind when you estimate labor for assembly.

1. Assemble the lowers

I assemble the sides and backs of the lower cabinets and then slide in the bottoms, just like with the uppers. There are strips of plywood that are brad-nailed and glued into the sides for mounting the countertop. If the cabinet side is visible, I only glue them. I also install the sub–toe kick by drilling pocket holes in the sides and top of the toekick material. I then glue and screw it in place. The cabinet maker supplies plastic corner brackets that are stapled to the cabinet corners with 3 ⁄ 8-in. narrow crown staples. Because I glue and clamp everything, I typically throw them in the garbage straightaway. For a drawer bases, I install the slides during the cabinet build. The cabinet backs and face frames are predrilled for slides so they’re easy to get in the correct position.

TIPS for smooth assemblySpace for staging cabinets Finding enough room to store completed cabinets while the glue dries can be a challenge in a smaller home. |

2. Build the drawers

I first apply glue to the dovetails on the ends of the drawer sides where they meet the back, and to the groove on the drawer bottom. I glue the back to the sides, slide in the bottom, and then attach the front. I attach the predrilled drawer front to the box front using the screws provided and then glue the front to the rest of the box. Sometimes you need to tap the pieces into place with a rubber mallet. Once everything is put together, I clamp the joints while the glue sets. I like to use a 23-ga. pin nailer to pin the bottom of the drawer box to the sides from the bottom to help hold things in place. Once the glue sets, I install the drawer latches on the drawer bottom with the supplied screws.

3. Install the lowers

Before installing base cabinets, I use a laser to check the floor for level and to figure out the highest spot in the floor. Starting at the high point allows me to shim low cabinets, which is far easier than cutting cabinet boxes that are too high. The cabinet tops must be level and coplanar to evenly support countertops. I use a stringline to keep the run of cabinets in a straight line and shim the boxes up and down and front to back as needed to keep everything level and coplanar. Once a run is in the correct position, I screw the face frames together and fully fasten the cabinet backs to the wall studs. Once all the base cabinets are installed, I install the doors, drawers, and crown and call to have the stone countertop templated.

The quality is also much better than the stocked cabinets at big box stores, though you are somewhat limited in color and style choices. For example, the manufacturer I use offers four door styles in three to four colors depending on which style you choose. They also offer some modifications to stock sizes and custom colors, but I haven’t used these services. I’m sure it increases cost and lead time.

Once you’ve assembled the cabinets you can move on to installing them, which involves the same process as installing any other kitchen cabinets. One of the advantages of using RTA cabinets is that you can have one or two people putting together cabinets and another person or two installing them. I recommend building your upper cabinets first so you can get them on the wall and out of the way while you build the lowers.

The kitchen’s worth of cabinets that you see in the photos in this article cost just over $4000, and took three carpenters a total of 8 hours to build and install.

Andrew Steele is a builder and remodeler in Purlear, N.C.

Photos by Patrick McCombe.

From Fine Homebuilding #311

RELATED STORIES

View Comments

I've found that construction adhesive is much more effective than wood glue In bonding RTA cabinet components. Clamp time can be greatly reduced, and the bond is much stronger. RTA cabinets are all we use in our multi-family projects, and they have proven to be very durable when assembled using construction adhesive.

This was an excellent article and I was very excited to ditch IKEA and online RTA cabinets and give kcdus.com a try. The article made it sound like the author, Andrew, was able to order the boxes he needed straight from KCD. I'm a GC and have everything I need for kitchen/bath design in-house. Just want to order the boxes. Unfortunately, when I contacted KCD, they told me I'd need to work with a local dealer. This added layer of cost and time removes the benefit. Andrew Steele, if you see this, can you let me know how you make this work? Thanks!