Make a Built-In Breakfast Nook

This custom-built bench offers seating, hidden storage, and a whole lot of charm.

Built-ins add functionality to any space, but few types offer as much day-in and day-out utility as a breakfast nook. For this project, the client had a compact kitchen that didn’t leave much room for a table and chairs. It was a space just begging for a breakfast nook.

A breakfast nook allows at least half of the seating around the table to be flat against the wall, eliminating the space needed behind chairs. It also allows the table to be tucked closer to the corner, opening up floor space, improving flow, and making the room feel bigger, all while offering additional storage. Unlike bookcases and window seats, a breakfast nook is a built-in that is likely to get daily use and abuse. So besides needing to be aesthetically pleasing, it has to be functionally designed and built to take a beating.

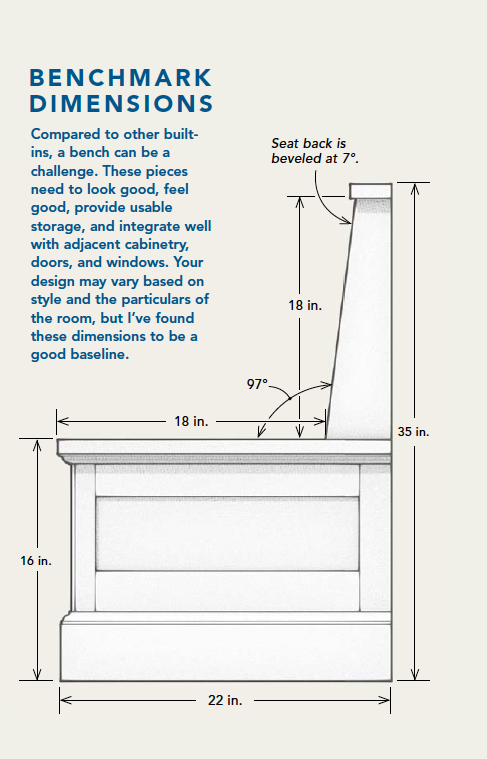

Dimensions to know

I’ve built enough breakfast nooks over the years to have a basic formula for dimensions. I usually aim for an 18-in. finished seat height, which includes cushions. Standard thickness for foam is 4 in., and I allow for about 2 in. of compression, so I usually design the bench so that the plywood below the cushions is 16 in. above the finished floor. For seat depth, I like 18 in. from the front lip to the lowest portion of the angled backrest. My designs don’t typically include a cushioned backrest, but if yours does, you will need to adjust this number to account for the added thickness.

While a straight back is easier to build (especially in a corner bench), a slight angle — 7° is what I used here — adds quite a bit of comfort and visual interest. If I’m tucking the built-in below a window, I prefer to use the window stool height as the top edge of the backrest, which in this case worked out to a comfortable 18 in. from the seat.

It’s typical to include storage in this style of built-in — drawers in the side or end of the unit, or lids that lift off or are hinged. I find that drawers and slides eat up a lot of storage space, so I prefer hinged lids.

With the critical dimensions and site specifics noted, I can flesh out the design and then begin fabricating parts in the shop.

Shop fabrication

The heart of this assembly is the plywood carcases, which not only serve as the storage areas but are the main components onto which the rest of the assembly is fastened.

I like the interior to be as presentable as the exterior, so I use prefinished cabinet-grade maple plywood for the carcases — 3⁄4 in. thick for the sides and back, 1⁄2 in. thick for the bottom — which also eliminates the need for painting the interior. I break the carcases into at least two equal sections (more for long runs) to ensure ample support. I generally avoid going more than 48 in. without adding a vertical support; for this project, a single center divider was sufficient. In the case of a corner unit such as this one, you also need to decide which carcase is going to run long into the corner. I usually run the shorter of the two benches into the corner.

In order to maintain the illusion of a true furniture leg, I set a recessed base assembly 6 in. from the front face. That’s far enough back so that you can’t see it, but shallow enough so that you can reach dust bunnies and runaway Cheerios. The base assembly is made from 3⁄4-in. plywood but is later skinned over with 1⁄4-in. MDF, so it provides a good opportunity to use scrap that has accumulated in the shop.

I build all of the bench-frame components with paint-grade European beech, which isn’t quite as soft as poplar but is easier to work than maple. Frames are assembled with pocket screws and are built a little oversize to allow for scribing and unknown site conditions. The same goes for the furniture legs; I cut the decorative curves in the shop but let the ends run long, leaving me wiggle room once I get to the site.

The frame-and-panel treatment on the front of the carcases includes a rabbet for the plywood panel, which goes up against the storage carcase and can therefore be glued and pinned to the frame rather than acting as a true floating panel.

To ensure purposeful reveals and proportions, I factor in the width of any moldings I plan to apply to the boxes once installed. For corner units, I need to consider which side of the front frame and furniture feet will overlap the other at the inside corner. I’ve learned that if I don’t address these matters during the design and shop-fabrication stages, those oversights will haunt me when I’m on-site.

At the job site

Once I’m on-site, my first step is to remove millwork and other obstacles, such as electrical devices, which are never OK to leave energized if they are to be buried behind a permanent piece of furniture. Next, I mark all the studs in the area by drawing vertical lines on the wall; this reduces the need to hunt them out one at a time later in the process. A little time on the front end saves me a lot in the long run.

I start the actual installation with the storage carcases, which are assembled in the shop with the recessed bases attached. Since all components are built off these boxes, it’s imperative that they be installed dead level, plumb, and square to each other (in the case of a corner installation).

With the carcases in place, I add the solid-wood frame components—first the frame that will support the lids, and then the frames and panels that dress up the front and sides.

The 7° back assembly is supported by a pair of angled nailers cut from quality, kiln-dried 2x stock. The upper nailer is attached to the wall just below the sill, and the lower nailer is fastened to a lid cleat that’s on top of the carcases below. Spanning the nailers is 3⁄4-in. CDX plywood, which creates a stiff subbase for another pocket-screw frame that is then infilled with solid-wood tongue-and-groove paneling for a traditional look.

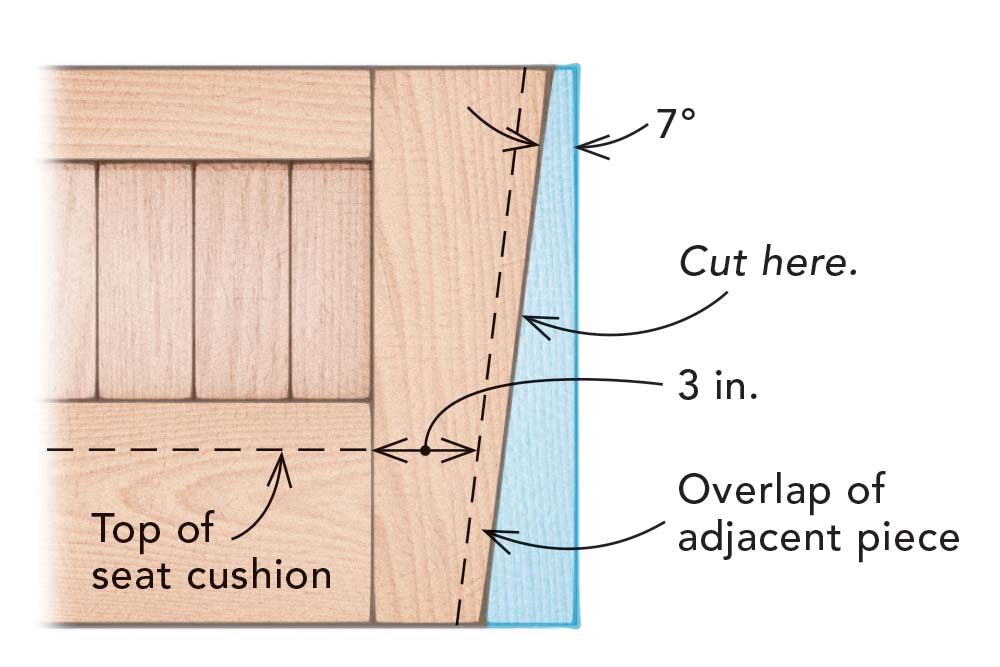

On the inside corner of the seatback, both stiles are cut at a 7° angle, with one piece lapping the other. I configure the seat-back frames so that they show 3 in. of stile at the narrowest point. The easiest approach to conquering this tricky layout is to draw a plumb line on the face of the plywood where you want the inside rail to stop and the paneling to begin (drawing above).

The edge cap on the bench should be 5/4 (nominal 1 in.) stock to match the backrest cap, and I like it to overhang the lower panel by 1 in. or so. This piece tends to see a lot of stress, so I like to glue, screw, and plug it.

Finally, I fabricate lids for the storage areas that also support the upholstered cushions. I use MDF with a biscuited and screwed solid-wood edge, which offers a stronger base for the piano-hinge screws than MDF alone. A simple finger hole through the top of each lid eliminates the need for hardware, and I rout all edges with an 1⁄8-in. radius bit to give them a nice feel.

The lids are best left loose until after the whole bench has been painted, which allows the painters access without having to work around the piano hinges.

Boxes create a foundation

As with any cabinet installation, time spent getting the assembled plywood carcases level, flush along their top edges, and square to each other at the corner pays dividends when installing the components that come afterward.

Angled back support

I like to align the bench back with the windowsill, which usually means removing part of the existing casing and making a new, deeper stool.

The trick for a tapered stile

For the backrest panel frame, start with an extrawide stile on one end to allow for the tapered cut necessary to meet the adjacent piece in the corner. I prefer to see 3 in. of stile at the narrowest visible point, which matches the width of the straight-cut stiles. To get an accurate measurement for this tricky spot, do your layout and take your measurements on the plywood.

Finishing touches

To dress up the benches and enhance their built-in, furniture-type look, I apply tongue-and-groove paneling to the backs, traditional furniture-style legs to the lower boxes, and simple detail moldings to ease some of the transitions between pieces. After I fabricate the lids, the piece is ready for paint.

Photos by Justin Fink and Nina Johnson. Drawings by Christopher Mills.

Related stories:

From Fine Homebuilding #262

For more photos, drawings, and details, click the View PDF button below: