Good-Looking and Long-Lasting Traditional Gutters

An extruded-aluminum gutter and matching rake trim recreate a classic eave-to-rake transition.

Synopsis: Before aluminum gutters were introduced in the 1950s, architectural wood gutters were the norm. One of these old gutter profiles, known as the Boston pattern, has a shape that allows for a smooth transition from a wood gutter at the eave to a matching rake trim with the same profile. With wood gutters eventually leading to too many moisture and rot issues, aluminum gutters rose in popularity, but were no longer aesthetically matched to their homes. Light House Design’s David Hornstein ended up manufacturing his own extruded aluminum gutter with a profile identical to the Boston pattern, called Duragutter, and in this article he explains how it is installed on a Cape undergoing a complete renovation and gutter installation.

One of the great things about living in New England is seeing the traditional architectural details on old houses, and that includes the gutters. Gutters used to be fully integrated into the overall trim scheme of a home. From modest bungalows to extravagant Victorians, gutters were a key architectural element, treated as moldings that defined the roofline and created a visually seamless continuity with other trim elements.

But there were seams—and that was part of their demise. Now known locally as the Boston pattern, a standardized gutter and rake trim first appeared around 1880 and was developed to simplify and standardize the process of putting on gutters and cornices. Its defining feature is the seamless transition from a beautiful wood gutter at the eave to a matching rake trim with the same profile. With the new system, lumberyards could sell a single gutter and rake profile that worked for a variety of roof pitches and overhang details.

Gutters and rakes made to match

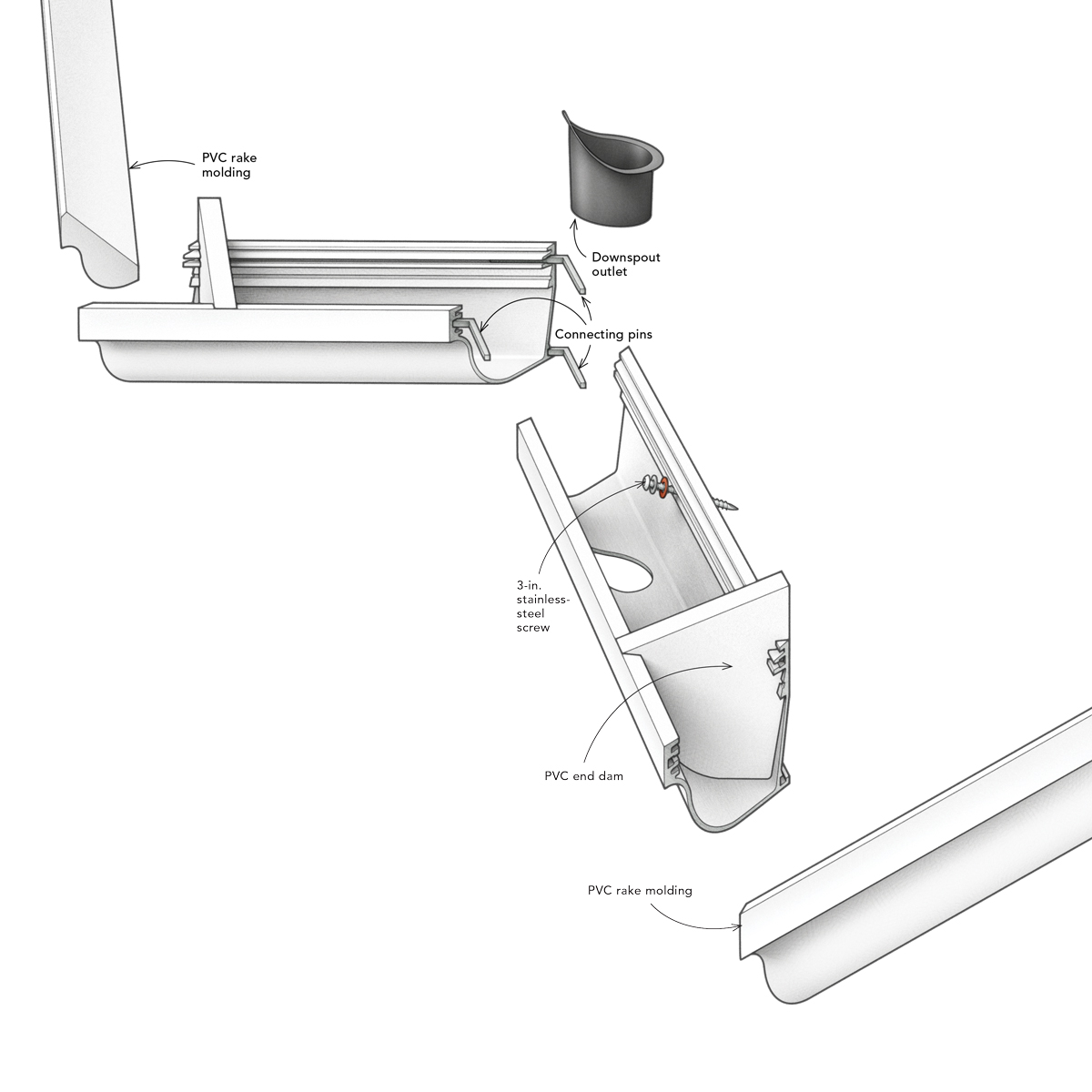

The sloping rake must mate up to the level gutter at roof corners, but their cross sections are different because one is horizontal and the other slopes. To get the two parts to line up at the miter, carpenters employ a number of strategies. You can use a gutter and rake with different widths. You can also adjust the spring angles to align the parts. The mill owners who introduced the Boston pattern figured out a brilliant solution to getting the two different cross sections to fit together. They modified the traditional ogee, making the top concave section smaller and extending the bottom section. This pleasing shape allows rake profiles to work with common roof pitches from 3-in-12 to 20-in-12 with a minimum of fitting at the rake miter. These gutter and rake profiles were used extensively, even during the Queen Anne era when rooflines had varied pitches and eccentric designs.

Build and hang the gutterThe overflow lip of the gutter lines up with the top surface of the roof sheathing, following the slope. This sets the rake at the right height so that it just touches the underside of the roofing. A pitch toward the downspout at 1⁄16 in. per ft. is essential with wood gutters, but unnecessary with these aluminum gutters. Join corners. The gutter extrusion has three channels that receive aluminum connecting pins for butt joints and miters. CA glue holds components together. Make cuts and drill for drops. The heavy-duty extruded-aluminum gutter is cut with a carbide-tipped blade on the miter saw with the gutter upside down on the sawtable, using a supplied block to raise the front edge. Holes for the outlet are made with a 2-1⁄2-in. bimetal hole saw. The drill must be held parallel to the gutter’s back to prevent an elongated hole. Activator speeds the bond. CA glue activator is sprayed on the glue joint and connecting pins, which hold the separate pieces together. Tape seals the deal. Butyl tape is cut and fit at joints and corners. The small pieces of tape are supplied precut for easier assembly. Install end dams. Plastic blocks are fit near rake transitions and sealed so water never reaches the mitered joint where the gutter meets the rake board. The blocks are angle-cut in the field to match the roof pitch. Glue the tube. CA glue is placed around the flange at the top of the downspout outlet. The outlets are ABS plastic, which is durable in warm and cold temperatures and UV-stable. Make the opening. The top of the downspout outlet is sealed with pieces of butyl tape that are rolled with a small roller for a strong bond. Then the downspout opening is cut with a knife. Hang assembled sections. With the outlets installed and the inside corner assembled, this section of gutter is ready for hanging. Fasten with screws. Three-inch stainless-steel structural screws are used to hang the gutter, with one screw per rafter. The screws have a T30 torx head and include a flat washer and a flexible sealing washer. |

Aluminum ends the Boston pattern

The joints, transitions, and downspout outlets on wood gutters were made watertight by carving out a recess on the inside for lead or copper flashing. Given the movement of wood, these joints would fail over time, leading to leaks and rot. Repairs required skilled carpenters and roofers, so when inexpensive, maintenance-free aluminum gutters came on the scene in the 1950s, wood gutters were quickly replaced.

There was one big problem, architecturally speaking: The profiles of aluminum gutters were different than wood gutters, so the new gutter could no longer integrate into the rake trim common to New England architecture. This led to some hideous hacking away of original details, compromising the integrity of many fine homes. Over time, many architects and builders forgot the historical details and developed new, “economized” versions that could be built with available materials. A few builders and design die-hards still insist on using authentic wood gutters, but unfortunately redwood and cypress have been replaced by less-durable cedar and fir.

Modern materials, less maintenance

It killed me to see botched gutter jobs on otherwise beautiful homes, and I was inspired to find a better solution. I ended up manufacturing my own, seen in the project in this article. It’s an extruded aluminum gutter with a profile identical to the Boston pattern, called Duragutter. It enables designers and builders to replicate traditional details with low-maintenance materials. There is also a square profile designed for contemporary homes, as well as a flat-bottom version.

This article showcases a Cape undergoing a complete renovation and gutter installation. It was designed by Chatham, Mass., architect Leslie Schneeberger of SV Design and built by Duffany Builders.

David Hornstein is a principal at Light House Design. Special thanks to John Moriarty of J. P. Moriarty & CO., Restoration Millwork in Somerville, Mass., for explaining the history of the Boston pattern.

Photos by Patrick McCombe.

RELATED STORIES

View Comments

1/16" per foot is 3.125" over 50'. A flat gutter will drain just fine, the only reason for a slope like that is for waterflow for washing itself out. The final product does look amazing. Cyprus is readily available, why not make another 100 year wood gutter?

Tried looking for the manufacturer online. Slight typo in the text. I believe it's "duragutter" (www.duragutter.com).