Understanding Types of Roof Vents

Ventilation is considered standard practice, but not all building scientists think vents do much or agree on the best ventilation products.

Synopsis: Builders typically install soffit and ridge vents on new houses per code specifications, on the promise that vents carry away moisture and heat, lower the risk of mold and rot, and make houses more energy efficient. However, the benefits of roof vents are debated.

A freshly immigrated Norwegian carpenter built our two-story house in 1931. It has a walk-up attic that can be aired out in the summer with a pair of windows in the gable ends. What the house doesn’t have is any apparent ventilation in the roof.

Houses like ours are an anomaly these days. Builders now typically install soffit and ridge vents on new houses per code specifications, on the promise that vents carry away moisture and heat, lower the risk of mold and rot, and make the house more energy efficient.

New standards are set

What brought on the fundamental shift in thinking about attic ventilation? Lots, says William Rose, senior research architect at the Applied Research Institute, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and author of Water in Buildings: An Architect’s Guide to Moisture and Mold. As Rose explained in a 1995 article, a number of changes in building materials and practices in the 1930s and ’40s got the ball rolling. They included the development of bituminous roofing materials that were impermeable to moisture movement, the introduction of plywood in roof decks, the wider use of cathedral ceilings, and greater levels of insulation.

In the late 1930s, a researcher named Frank Rowley concluded that condensation in walls and attics could be reduced with ventilation. The current ventilation standard for roofs appeared out of nowhere in a 1942 National Housing Agency document titled Property Standards and Minimum Construction Requirements for Dwellings. It specified a 1/300 ratio of ventilated area to total area of the space. Then in 1947, a researcher named Ralph Britton of the Housing and Home Finance Agency, the federal agency that preceded the Department of Housing and Urban Development, used the 1/300 standard in a series of tests on wall and roof assemblies. This ventilation rate was included in a table of recommended building practices in a report that Britton authored in 1949. The 1/300 rule has been with us ever since and is now codified in the International Residential Code (IRC).

The benefits of venting are debated

Builders go to a lot of trouble to vent the roof. Whether it’s effective or not depends in part on exactly what a builder is trying to vent—an unconditioned attic where the insulation and air barrier are immediately above the living space of the house, or the roof deck when the air barrier and insulation have been moved to the roof plane. Due to increased insulation requirements in the 2021 iteration of the building code, the latter assembly has become even more challenging to ventilate properly while hitting prescriptive R-value targets when framed conventionally, pushing more builders to consider unvented roof assemblies (see “Creating low-risk unvented roofs,” ).

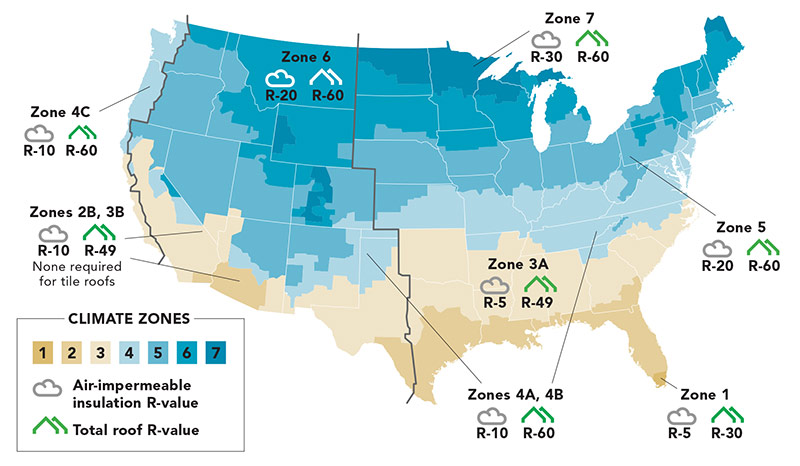

Creating low-risk unvented roofsThe 2021 International Residential Code (IRC) brought about significant changes for ceiling-insulating values. The code now requires R-values as high as R-60 in climate zones 4 and above. This adjustment aims for better thermal performance, reduces energy consumption, and enhances occupant comfort, but it comes with challenges for builders. If you’re framing a conventional roof with 2x10s, for example, and striving for a 1-in. vent space beneath the roof deck, it will be hard to meet required insulating values in the ceiling. You could offset the deficiency in the ceiling with more insulation in other areas and see if you meet the “Total UA alternative,” which is another viable option in the prescriptive code. Or you could create an unvented assembly with robust insulation below and/or above the roof sheathing without any ventilation at all. The building code permits unvented roofs so long as you use the right amount and type of insulation to prevent conditioned air from condensing against the back of the roof sheathing. For instance, in colder climates—zones 5 and above—any air-impermeable insulation needs to be a Class II vapor retarder, or have a Class II vapor retarder coating or covering in direct contact with the underside of the insulation. Otherwise, the code calls for sufficient amounts of air-impermeable insulation by climate zone in table R806.5 of the IRC to be used in conjunction with the overall insulating requirements in table N1102.1.3. We’ve listed both here. |

The easiest scenario to ventilate is an unconditioned attic—what building scientist Joseph Lstiburek calls “one of the most underappreciated building assemblies that we have in the history of building science.” As long as the builder is careful about a few details, this approach is “hard to screw up,” as Lstiburek explained in his 2011 article “A Crash Course for Roof Venting.”

Venting gets more complicated when the attic is conditioned or in vaulted ceilings above conditioned living spaces. Here, the ventilation, air-sealing, and insulation all converge in a very condensed zone at the roof deck. No matter where the thermal boundary of the attic starts and stops, the air barrier that protects the roof deck from moisture and condensation is very important—more important than ventilation. Or as Rose puts it, roof venting has diminishing importance as airtightening becomes more effective. Rose has observed that roof vents have a minimal impact on shingle life. Vents don’t lower shingle temperatures in summer substantially, nor are they effective in eliminating ice dams in winter.

“[When] the code requires vents, people put them in (or not) and they move air (or not) and it all works, because attic problems are rare,” Rose said in an email. “Does air flow through vents? Some air, but not much, because if a lot of air came through, then so would a lot of snow. So vents don’t allow much airflow. This was research we did in the early ’90s. We didn’t publish it because it would lead most people to think we cared about whether something is vented or not, and we didn’t (and don’t).”

There also are some reasons to dislike vents. Vents are an added expense for builders and their customers, they take time to install, and, Rose says, they carry an energy penalty in both northern and southern climates. He adds that they “severely compromise resilience” in areas subjected to extreme weather events—wildfires, hurricanes, and tornadoes.

Andre Desjarlais, the Building Envelopes Program Manager at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, shares some of Rose’s views, and both agree that an effective air-seal below the attic is essential for controlling moisture that could condense on the back side of cold roof sheathing. But Desjarlais thinks that vents do have some value.

“From an energy perspective, I’m not sure ventilation is much of a big deal,” he said in a telephone call, “but from a moisture-control perspective, I think it is a big deal.”

While attic ventilation is a complex topic that has received a lot of attention from building scientists, we shouldn’t expect consensus anytime soon. “Questions will always arise with squeezed assemblies that try to incorporate airflow,” Rose said. “I wouldn’t pretend anyone has answers for all of those questions.”

With this in mind, builders still need to know how to ventilate roofs successfully and how the products available from manufacturers such as Cor-A-Vent, Owens Corning, GAF, CertainTeed, Benjamin Obdyke, and Air Vent can help satisfy the requirements when the project calls for it.

How much venting is enough?

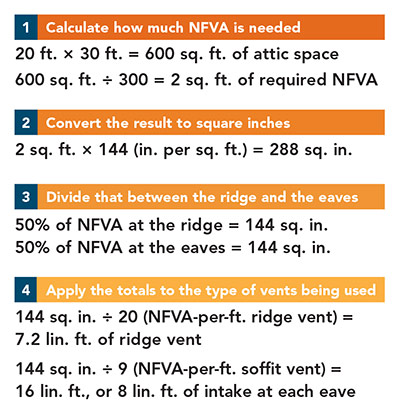

In practice, the 1/300 rule calls for a builder to divide the floor area of the attic (in square feet) by 300 to get the total square footage of required net-free vent area (NFVA). Manufacturers usually recommend a balanced approach to installing the vents—that is, roughly half of the total should be in the form of ridge vents, with the other half in soffit vents. Using values provided by the vent manufacturer, the builder can then determine how much of a given venting product to employ to meet venting requirements (see “How much airflow do you need?”).

How much airflow do you need?Net-free vent area (NFVA), a spec for roof-venting products, is the area of a vent that allows air to flow through it. The IRC describes the 1/300 rule for roof venting as the ratio of vented attic space to required NFVA. Once you’ve done the math, you have to determine where to put the vents. It’s common for about half of the NFVA to be at the ridge, with the other half split between the eaves. In fact, in climate zones 6, 7, and 8, where a Class I or Class II vapor retarder must be installed on the warm-in-winter side of the ceiling, having between 40% to 50% of the required NFVA within 3 ft. of the ridge or highest point in the space may be required. The balance goes in the bottom one-third of the roof. Do the math Using a house with a 20-ft. by 30-ft. attic floor as an example, here’s how to calculate the venting requirements at the ridge and eaves. |

In the case of a conditioned attic or a vaulted ceiling, where the air barrier moves up to the roof plane and each rafter bay is insulated, you may think you need to calculate the square feet of the two roof planes, which would be substantially greater than the square feet of attic floor. This is not the case, says Cor-A-Vent’s sales and technical staff member Thomas Osborn. Osborn says the company advises builders to use the same numbers they would for a simple unconditioned attic. However, because the rafter bays in a conditioned attic are isolated from each other, every rafter bay needs to be vented. In these situations, continuous venting products installed at the eaves and ridge are a common option (otherwise, you’d have an awful lot of louvers or turbines on your roof). This also means installing continuous vent channels above the insulation and below the sheathing, from eave to ridge, in each rafter bay.

In a conditioned attic, with insulation between the rafters, two things should occur. First, the bottom side of the rafters should be airtight so that warm, moist air does not migrate through the insulation to the sheathing. Second, the ventilation channel above the insulation should be a minimum of 1 in. deep. (Some experts are happier with a 2-in.-deep space.) These spaces can be created by site-built or commercially available baffles, which should be robust enough not to be crushed when insulation such as dense-pack cellulose is added.

One other detail comes from Paul Scelsi of Air Vent. He recommends that as the roof pitch increases, so should the amount of ventilation. “Current IRC requirements do not factor the role a roof’s pitch plays in the amount of attic ventilation needed,” he says in a 2015 article in Roofing, “but ventilation manufacturers do.”

Because the volume of air inside the attic increases with pitch, he suggests using a 1/150 standard for roofs up to a 6:12 pitch, then increasing it by 20% for roofs between 7:12 and 10:12, and by 30% for roofs with a 11:12 or higher pitch.

These ventilation guidelines are for “steep-slope” roofs with a pitch of 3:12 or greater. If you’re confronted with a flat roof, the approach to the assembly changes considerably. According to Rose, research has found that low-slope roofs should not be built as vented cavity assemblies. Getting air to flow through a horizontal cavity by natural means is just too difficult to yield the intended benefit in a flat-roof assembly.

SOFFIT AND RIDGE VENTS are the standard

Most roof venting is done by combining soffit and ridge vents. This balances incoming and exiting air, as codes and manufacturers suggest. Soffit intake vents come in several types, from round ports that are inserted into holes drilled through the soffit to continuous 2-in.-wide plastic or aluminum vents installed with the soffit material.

Some buildings have no soffits, making it difficult to use conventional products. Cor-A-Vent, CertainTeed, Owens Corning, and Air Vent all make products to troubleshoot this.

Ridge vents cover a slot created by cutting out the sheathing on both sides of the ridge. Vents come in rolls or as individual sections that are butted together. Shingles nailed over the top of a vent conceal it mostly from view but expose a continuous strip of vent area at the lower edge. Manufacturers typically offer more than one width and may offer versions with an internal filter designed to be more resistant to wind-driven rain and snow. Ridge vents with a Class A fire rating are available. Jeff Avitabile of GAF says ridge vents that come on a roll are easy to install and that they can be used in all climate zones. However, ridge vents that come as 4-ft.-long rigid panels often have higher NFVA values and are less likely to be compressed during installation.

POWER VENTS come with risks

Most roof vents on the market are passive devices that rely on the stack effect, wind, temperature differentials, or some combination of those forces to move air. There also are electrically powered vents capable of moving a great deal of air, such as the roof-mounted models manufactured by Air Vent that can exhaust as much as 1320 cu. ft. per minute (cfm). Powered gable vents can push up to 1620 cfm. These fans are triggered either by temperature or by humidity. Air Vent says these products are an efficient option to replace turbines that are already in place. GAF recommends a power vent as the sole means of exhausting air—that is, not to be used in conjunction with some other type of exhaust vent—on roofs with limited ridgelines or where homeowners want to reduce attic temperatures. However, Jeff Avitabile of GAF says it’s extremely important that adequate makeup air be provided, not only to protect the motor from overheating but also to minimize the risk that conditioned air will be pulled from the house through leaks in the ceiling.

That possibility is exactly why power vents have their critics. One of them is former Green Building Advisor editor Martin Holladay. “Although the logic behind powered attic ventilators is compelling to many hot-climate homeowners, these devices can cause a host of problems,” Holladay wrote. The reason is that the powered vents depressurize the attic, and it’s hard to know where the makeup air will come from. That could be conditioned air from the house, which would result in increased cooling costs, or flue gases from a water heater. There is also research indicating that the fans use more energy than they save in reduced cooling costs, and while solar-powered options are available, they don’t resolve the other potential problems.

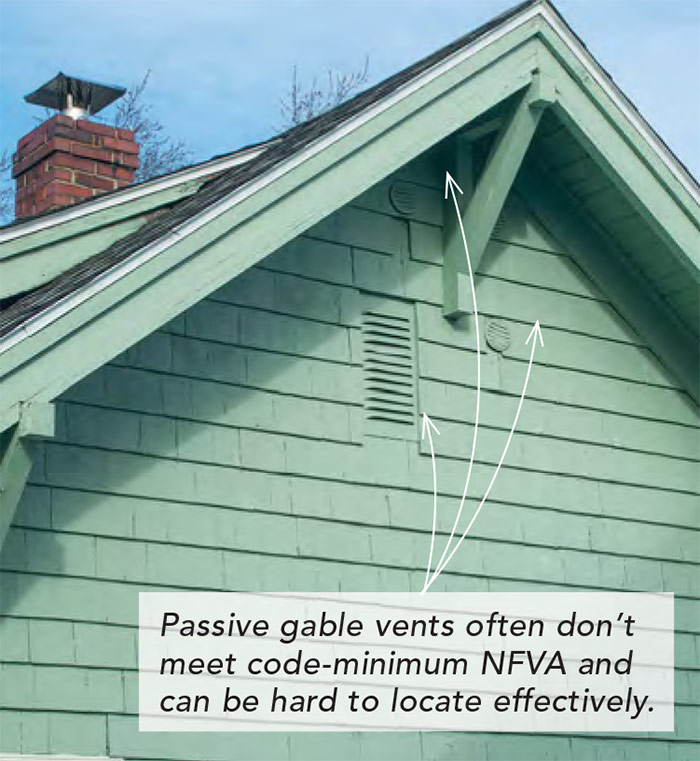

GABLE VENTS are common in older homes

Interest in gable vents is waning, says Jeff Avitabile of GAF, who does not consider them a preferred first choice. One drawback is that they provide spot ventilation rather than the continuous ventilation that a soffit-to-ridge approach would theoretically produce. In addition, they are not installed at the highest point of the attic, which might limit their effectiveness.

As a result, Avitabile said, gable vents should really be considered a secondary option that can be used when other vent types are not practical or when an older gable vent is being replaced. Still, if you’re going strictly by the numbers, gable vents are available with NFVAs high enough to satisfy the IRC.

ROOF TURBINES AND LOUVERS can be effective options

Roof louvers and turbines such as those from Air Vent and Owens Corning have ventilation rates as high as 50 to 95 sq. in. of NFVA, but they don’t provide continuous venting, and you still may need a number of them to meet the venting requirements in the codes.

Because they pick up exhaust air from a single point, they’re a better choice for unvented attics than they are for an insulated roof deck, unless you are willing to install one in every rafter bay. They are common on older houses and houses with short ridgelines

Turbine vents are an old design and can be charming when made of copper. But determining their effectiveness when compared to other ventilation types isn’t straightforward. To do so, you would need testing data that measures ventilation rates above and beyond what the opening in the roof provides. I wasn’t able to locate any such data, so the safest practice is to use the NFVA but not count on any added benefit from the spinning turbine blades. Cor-A-Vent’s Thomas Osborn says turbine vents aren’t as common as they once were, as builders continue to shift to soffit-to-ridge venting options. GAF views turbine vents as a niche product that sells briskly in Florida, Texas, and along the Gulf Coast.

50 sq. in. of NFVA.

SPECIALTY VENTS are made for difficult places

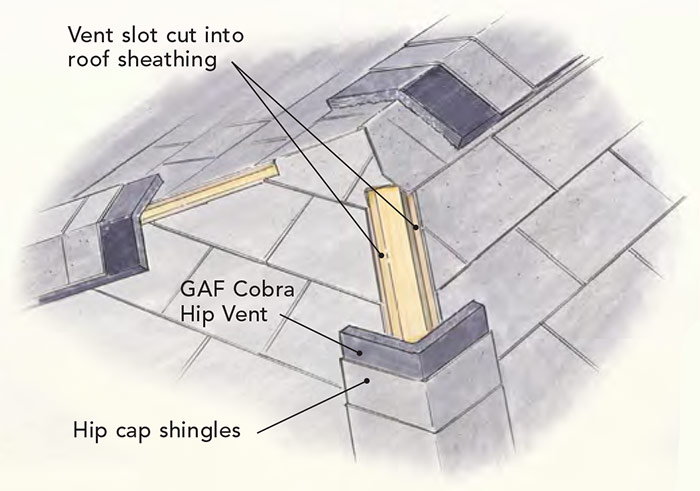

Simple gable roofs are easy to vent by establishing an unbroken air channel from the eave to the ridge. Hip roofs and roofs that run into a wall are more challenging. Manufacturers offer specialty vents for these situations. “All roof assemblies can be ventilated in some way,” says Dale Walton of CertainTeed. “It may not be balanced or function perfectly, but the attempt is made.”

Vents made for hip roofs take care of a spot in the framing where the jack rafters die into the hip rafter. The vent acts just like a ridge vent. Air Vent’s version, the Hip Ridge Vent, comes in 4-ft. sections with an NFVA of 12 sq. in. per ft. Just like a ridge vent, it is shingled over to expose a narrow opening. GAF’s Cobra Hip Vent stands at just 5⁄8 in. tall and has an NFVA of 9 sq. in. per ft.

A hip vent is similar to but not the same as a ridge vent, says GAF’s Jeff Avitabile. GAF developed its version for houses that had very long hip rafters but very short ridgelines, which makes it hard to meet code-required ventilation with a soffit-to-ridge system. The vents are designed so that water running down the roof has a way of exiting the vent more effectively than would be possible with a ridge vent. A hip vent should be installed in the upper part of the hip, according to GAF.

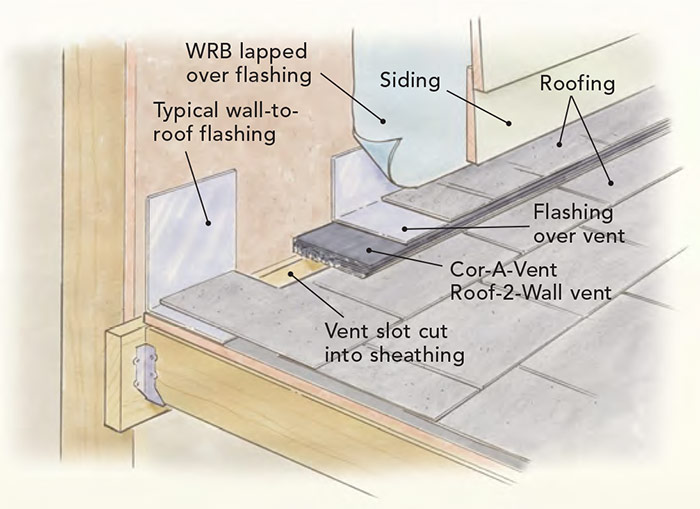

For roofs that run into walls, Cor-A-Vent developed the Roof-2-Wall vent that fits over a slot cut in the roof sheathing just below the roof-wall intersection. The rafter bays that normally would simply stop at the wall line now have a way of exhausting air.

From Fine Homebuilding #319

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below.

RELATED STORIES

- Attic Ventilation Strategies

- A Crash Course in Roof Venting

- Roof Venting Doesn’t Affect Cooling Loads

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Roofing Gun

Shingle Ripper

Ladder Stand Off