The Counterintuitive Cladding

A builder of environmentally responsible affordable housing makes the case for vinyl siding.

Justly or unjustly, we in the green building movement are often viewed as self-righteous. Most often we are at the forefront of the truth, introducing new building methods and specifying materials that not only protect the environment but improve building quality. Other times we get it wrong. For example, in pursuit of energy efficiency, we wrapped interior walls in plastic sheathing to prevent air infiltration. This unwittingly trapped moisture in the walls, promoting mold and causing “sick building syndrome.” But we learned, and we fixed it.

It’s harder when we’re wrong about something that contradicts our favorite beliefs. We remain staunchly unwilling to look askance at finishes we love, such as brick and bamboo, and even less likely to reconsider those we love to hate, such as vinyl siding, even when our beliefs are proven wrong.

Some in the green building community reflexively reject vinyl siding because it’s a plastic finish. They believe it’s made of petroleum, releases dioxin during manufacture, and that it is flimsy – none of which is true. And what’s worst, it’s, well… you know, made of plastic and, well… Yes, it is plastic, but that does not constitute an environmental sin. Every major green building certification program allows vinyl siding and awards points for its use.

Why the contradiction between popular lore and the most stringent certification programs? Because intuition can be wrong, and how we feel about a product – like it or not – does not always reflect the truth.

Green by all Credible Definitions

One description of sustainable cladding involves materials or prefinished assemblies that do not require chemical finishing products to be applied on-site, such as paints and stains, reducing a building’s environmental impact over both the short and long term by effectively remaining maintenance-free, at least in relative terms.

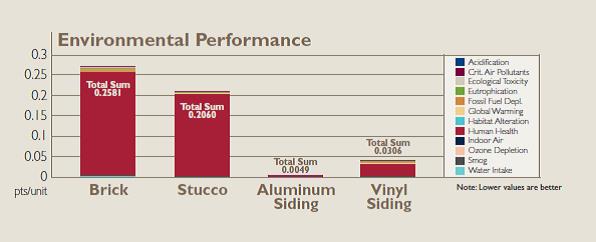

Much stricter criteria to judge green building products are based on a lifecycle assessment. Here it’s hard to argue against vinyl siding because tests using Building for Environmental and Economic Sustainability (BEES®) software – the green industry gold standard for lifecycle impact assessment – shows vinyl siding outshines most other popular claddings, including fiber cement and brick, falling short only to cedar siding. Fiber cement, such as Hardie Plank, is among the worst environmental options, yet many in the green building movement reflexively embrace it.

Whenever an architect or green building advocate is tasked with looking into green bona fides of vinyl siding, they almost always come out with a moderate view, if not embracing the material, they conclude with something along the lines of, “…it’s okay sometimes and if you have to.”

For example, this weekend I read a blog post by a prominent green building guru who had just remodeled his shop and finished off the exterior with vinyl siding. The blog was a confession of sorts, and an explanation of his choice – the material is durable, requires no ongoing maintenance other than the occasional wash with mild detergent, was safe to homeowners, etc. Unfortunately, he concluded that he felt sorry for those living near the vinyl plant that made his siding. His sympathies are unwarranted and misguided.

Vinyl siding plants are not the same as old vinyl manufacturing plants in general and they do not spew dioxin into the air as portrayed in the movie “Blue Velvet” that triggered the anti-vinyl siding movement in the first place. But, even if the toxic argument were true, why don’t I hear the same green gurus fessing up to the damage caused by the expanded polystyrene in their structural insulated panels, or the PVC in their house wrap and drain pipes or the horrors of the foam sheathing we are now required to use?

Why You Should Not Hate Me for Using Vinyl Siding

In Colorado, where I live and work, a movement to ban vinyl siding has taken root in at least two communities, Fort Collins and Erie, and this may spread. As a builder of environmentally responsible affordable housing, this limitation means I cannot avail myself of a legitimate, green building option that helps me to keep costs in line for my low to moderate-income buyers.

When push comes to shove – and I’ve had to push and shove to get vinyl siding into some of my projects – the objections come down to esthetics. You might think you don’t like the look, but I do, and once you’ve seen one of my houses, you will, too. That’s because I know how to use the material tastefully. To wit, my vinyl-sided homes have won green building awards and graced the pages of magazines such as Fine Homebuilding and Dwell.

Any material has its place, and design and construction quality always trumps material specifications for aesthetic and environmental performance. Like vinyl siding, plastic laminates were once considered inadequate environmental and architectural products – that is until popular architects, such as Sarah Susanka began specifying plastic laminate surfaces that featured beautiful prints. Now plastic laminates have become an accepted material in high-end architectural and green building projects.

The same is happening with vinyl siding, albeit more slowly. Last year I attended the Congress for the New Urbanism in Buffalo, NY, and toured boutique, high-end subdivisions that featured vinyl siding. I say “featured” because when I asked one builder why he chose this cladding, he said his affluent buyers were mostly senior citizens who had owned a number of homes during their lives, and would not consider any other product due to vinyl siding’s longevity and relatively low maintenance requirements in the harsh climate of upstate New York.

One architect commented they had experienced the same thing in Wisconsin, where after researching many siding options, he opted for vinyl siding for long-term durability.

I have seen the results of vinyl siding bans at work in low-income neighborhoods in Omaha and New York. The city invests tax dollars in revitalization, misguidedly specifies fiber cement to appease environmental and architectural misconceptions, and five years later the new neighborhood looks as bad as the distressed neighborhoods surrounding it. There’s no money for ongoing maintenance, and apparently no willpower for exterior upkeep, even among the well-heeled.

My neighborhoods, 20 years later, still look new. Just the way I like it and so would you.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Handy Heat Gun

Affordable IR Camera

Reliable Crimp Connectors

View Comments

Great piece, Fernando. Lifecycle assessment is a very useful tool.