Laying Bluestone over a Wood-Frame Floor

Tile pro Tom Meehan explains the process of installing a bluestone floor, from prepping the substrate to sealing the stones.

Q:

I want to lay bluestone over the wood-frame floor of my new addition. The stones are irregular shapes and vary in thickness from 3/4 in. to 1-1/2 in. How should I prepare the floor under the stone, and what tips can you give me for laying it down?

Kevin Ireton, New Milford, CT

A:

Tom Meehan, a tile installer in Harwich, Massachusetts, replies: Installing irregular bluestone is difficult and backbreaking work, but the process is really fun and the results rewarding.With the varied sizes and irregular shapes of the stone, working with it is sort of like doing a jigsaw puzzle with giant pieces, only you get to determine the final picture.

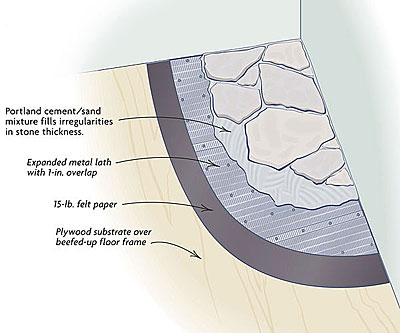

The first step is preparing the floor.The bluestone will add a lot of weight to the floor, so make sure that the substrate is strong with no bounce or deflection. I staple 15-lb. felt paper to the plywood subfloor, and then I staple or nail (with 1-1/4 in. roofing nails) galvanized metal lath over the felt paper. I overlap the metal lath sections a full inch. I do not recommend using cement backerboard under bluestone.

Next, I dry-fit the pieces of stone on the floor. This step is the most time-consuming part of the process, and a great deal of consideration should be taken to get the pieces arranged according to size and color.The thickness of the stone will vary, but I don’t worry about that yet. As I fit the stones in place, I use blackboard chalk to number them in one corner and then draw a simple map that lets me stack the stones out of the way as I am working.

As I cut the stone to fit, I like to leave a consistent 1-in. grout joint, but I’ve seen beautiful installations where the grout joint varies in size.To cut the stone, I use a grinder with a 4-in. diamond blade. If you want a more natural-looking edge, you can also score the stone about halfway through on the back, turn it over and snap it over the edge of a sawhorse.Another alternative for cutting bluestone is using a worm-drive circular saw outfitted with a wet/dry blade. Bluestone is soft enough that you can usually cut through it on a single pass.

After the stones are cut and dry-fit comes the moment of truth: cementing the stones in place. In a mixing box, I put 20 shovels of masons’ sand to one 94-lb. bag of portland cement. I first dry-mix the sand and cement thoroughly and then slowly add about 4 gal. or 5 gal. of water.

If you are at all concerned about the stiffness of the floor, you might consider substituting a latex admix for the water. It will increase the cost considerably, but it makes the floor stronger and more flexible. The mix should hold firm in your hand and not crumble. A little too wet is better than too dry.

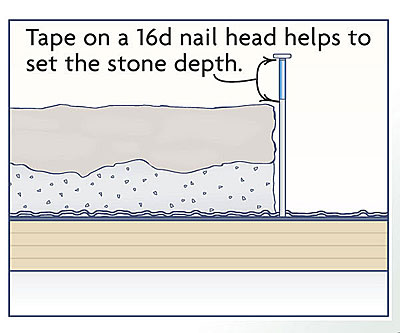

Dump enough of the mix on the floor to take care of a few stones at a time, and spread the mix evenly about an inch thick with a mason’s trowel. Check the thickness of each stone, and vary the depth of the mix accordingly. But put in more than you need, and don’t pack the mix down; you want the stone to start out too high.Next, jiggle the stone back and forth, or use a few good hits from a rubber mallet to settle the stone to its proper height.To gauge the correct height of the stone, I snap chalklines around the edge of the room. In the middle of a room, I simply use a 16d nail with a piece of tape around it. Registered against the subfloor, the nail works like a miniature story pole. A 4-ft. level is also handy for keeping the stones even, and in a really big area, you may want to use a transit. Shoot for an average of at least 1 in. of mortar under each stone.

Before each stone goes down, I skim-coat the back with a loose mixture of portland cement and water, mixed separately in a bucket. You could also use thinset here. This mix will bond the stone to the floor forever. I stay off the stone for 24 hours to keep from breaking the bond.

Grouting the stones is the most tedious part of the job. Unlike when I grout tile, I try to keep the stone as clean as possible.The grout mixture I like to use is 50/50 portland cement and sand. I make the mix the same consistency as the setting mix and push it directly into the joints with a pointing trowel. I clean the stone carefully with a damp sponge while the grout is wet, but I try not to use too much water. Alternatively, some people grout the stones as they lay them, allowing the setting-bed mortar to ooze up between the stones. I haven’t tried this technique, but it would save a tedious step. Again, sponging the stones with water to keep a haze from forming would be critical.

If the stone still needs to be cleaned, let it sit for four days, and then wash the stone with a 5:1 solution of water to muriatic acid. Wear goggles and rubber gloves, and apply the acid wash with a scrub brush about 20 sq. ft. at a time. Always double-rinse the stone with clean water.

There are two types of sealer you can apply to a stone floor. Topical sealers seal only the surface and leave a wet look. I’ve had good luck with Masonry Lusta (Silpro Corp.; 800-343-1501; silpro.com). If you prefer a dry or natural look, use a penetrating sealer such as 511 Impregnator (Miracle Sealants; 800-350-1901; www.miraclesealants.com).