A Beginner’s Guide to High-Performance Windows

There’s lots of published performance data on windows. Here’s how to use the information.

Few phrases are batted around as casually, and with such little precision, as “high-performance windows.” If you’re building a net-zero house or seeking Passive House certification, high-performance windows will be a given. Taking on a major renovation of an existing home? High-performance windows are probably part of the plan.

In reality, there is no such thing as a high-performance window that’s suitable for all climates, all housing types, and all solar orientations. “Manufacturers are going to define ‘high performance’ as they see fit,” says Steven Urich, director of programs at the National Fenestration Rating Council (NFRC). “There’s no standard definition for it across the industry, as far as I know.”

As important as windows are to the overall building enclosure, they are but one of many components that have to work together. The ideal window for one part of the country may not work as well in another.

“It’s the whole-house concept, which is what Passive House is trying to get at,” Urich says. “This idea that windows alone, your HVAC system alone, insulation alone [will be the end-all solution is unreasonable; no single component can] determine the energy efficiency of your home.”

Performance ratings for windows are a combination of several factors. The glass, or glazing, is key because it takes up most of the overall area of a window. Insulating glass is amazingly diverse, ranging from simple two-pane assemblies of clear glass to multi-pane sandwiches with low-e coatings and gas infill, all with different performance characteristics that can be tuned for a specific application. Other key parts are the window frame, the spacers between the panes of glass, and the hardware that ensures a tight seal.

Reading the NFRC label

The NFRC is a non-profit industry group that tests window performance and publishes the results to help builders, designers, and homeowners choose wisely. Participation by manufacturers is voluntary, although NFRC certification is required for Energy Star qualification. Each window the NFRC certifies carries a label that quantifies window performance in four ways. Here are the categories:

- U-factor. A number from 0.2 to 1.2, the U-factor is a measure of how well the whole window (not just the glass) stops heat flow. It’s the inverse of the more familiar R-value, which indicates the thermal performance of insulation. The lower the number, the more thermally efficient the window. As an example, a window with a U-factor of 0.18 has an R-value of about R-5.5.

- Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC). These values range from 0 to 1 and describe the amount of solar heat the window allows to get inside. Windows with high SHGCs don’t block much heat from the sun. Windows with low SHGCs are more effective at keeping out solar radiation.

- Visible Transmittance. Also a number between 0 and 1, this represents the amount of the visible light spectrum that gets through the glass—the higher the value, the more light that gets in.

- Air Leakage. This certifies that the window allows no more than 0.3 cubic feet per minute per square foot of window area in the equivalent of a 25 mph wind.

If high performance means energy efficiency, the two most important metrics are U-factor and SHGC, Urich says. The U-factor is a direct measurement of how much heat flows through the window. If you are building or renovating a house in a northern heating climate, a low U-factor is important. Even the most efficient windows can’t match the thermal efficiency of a well-insulated wall, but the lower the number the better. U-factors become a less acute issue in the South, where differences between inside and outside temperatures are less dramatic.

Regional climate differences also are important when looking at the SHGC, Ulrich says. In cooling climates, lower SHGCs keep more of the sun’s heat outside. That should make a house more comfortable and easier to keep cool. In the North, letting more of that solar energy inside the house amounts to free heat during the winter. One factor that designers have to contend with is that as thermal efficiency goes up, solar heat gain often goes down; that is, the lower the U-factor, the lower the SHGC tends to be.

The NFRC maintains a product directory at its website where buyers can look up the performance data on any certified window.

Understanding Energy Star windows

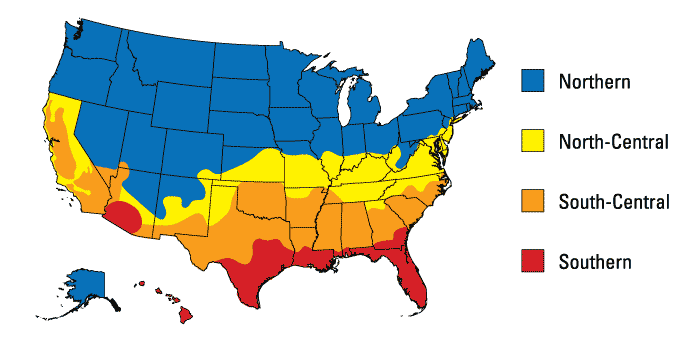

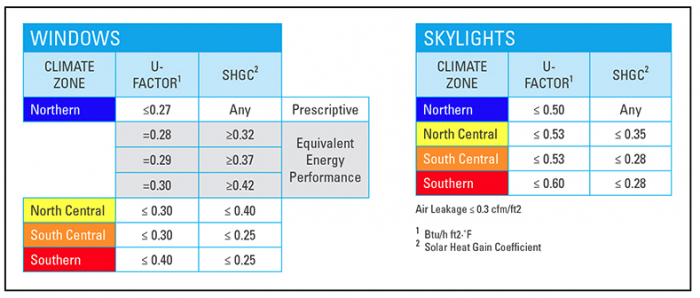

Energy Star, the Department of Environmental Protection program aimed at improving energy efficiency in a range of products, sets minimum requirements for qualifying windows. Like model building and energy codes, Energy Star divides the country into climate zones and assigns minimum performance numbers for each one. If you live in the Deep South, an Energy Star qualifying window will look much different than one you buy in Bangor, Maine.

Energy Star also has established separate criteria for a “Most Efficient” window classification, a next tier up, also broken out by the same geographic zones. In all zones, the maximum U-factor is 0.20, which equates to an R-value of 5.0 SHGCs range from 0.20 or more in the North to 0.25 or less in the South. These are significantly better values than standard Energy Star minimums.

To what should these numbers be compared? For baseline values, the minimum performance allowed by the most current version of the International Residential Code (IRC)—listed in Table R402.1.2)—range from 0.50 in Climate Zone 1 (the warmest part of the U.S.) to U-0.30 in Climate Zones 3 and up.

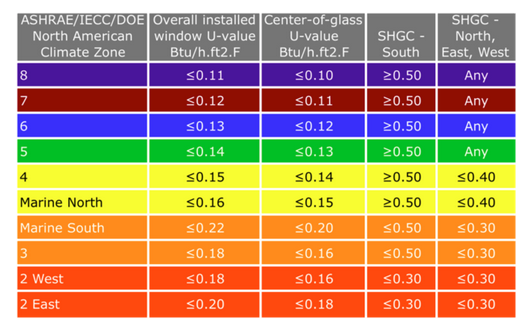

The Passive House Institute U.S. (PHIUS) has developed its own recommendations for window performance based on climate. The zones align with a map developed for the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) and used by the Department of Energy (DOE), rather than the simplified version used in the Energy Star program. It’s also helpful to remember that the recommended U-factors and SHGCs are for houses that will meet PHIUS certification standards. In other words, much more energy efficient than conventional construction.

Double vs. triple pane

Window manufacturers typically offer several glazing options in the same window line. Double-pane units with low-emissivity coatings on the glass were once the best that buyers could get, but triple-pane units have become increasingly common, and some manufacturers offer quad-pane units or windows that combine glass and suspended plastic films to create multiple insulating chambers and very low U-factors.

In cold climates, two important variables when choosing among these many options are how much of the exterior walls will be glass, and which direction the windows face, says Marc Rosenbaum, an energy expert and a mechanical engineer with the South Mountain Company on Martha’s Vineyard.

For windows manufactured in the U.S., the glazing is a better insulator than the frame. Glazing accounts for roughly 70% of the total window area in a standard residential window, Rosenbaum says, so in houses with big expanses of windows the difference in thermal performance between a double-pane and a triple-pane unit widens. “The triple glazing has close to double the insulating value,” he said in an email, “so the other big effect is human comfort due to the difference in radiant heat loss to that glass.”

The more the house faces south and the more glazing is concentrated on the south side, the more solar heat gain matters, Rosenbaum continued. By specifying windows carefully, it’s possible to get the benefits of a higher insulating value (a lower U-factor) with a triple-panel unit while retaining most of the solar heat gain you’d get with a double-pane unit.

Triple-pane units with a U-factor of 0.17 (the equivalent of R-5.8) are readily available. If that’s not enough, increase the number of glass panes or add suspended films. Alpen High Performance Products, for example, advertises a fixed window with a full-frame U-factor of 0.10 (R-10) and an operable window with a U-factor of 0.14 (R-7.1). A Canadian manufacturer, LiteZone Glass Inc., makes a fixed window with a center-of-glass R-value of 19.6—almost the same as a 2×6 wall insulated with fiberglass batts. (The catch is that the window is more than 7 in. thick.)

The European factor

U.S.-made windows are manufactured in several familiar styles—casement, double-hung, and awning among them. Fixed units (windows that don’t open and close) aren’t as leaky and are better insulators than operable windows. Casement windows, in which the sash closes tightly against the frame, are typically more airtight than windows with sliding sash.

Designers of Passive Houses and other superinsulated buildings often specify another type of window, one that’s common in Europe but not as well known in the U.S. market—the tilt-turn. These windows can be operated in one of two ways, either by turning the latch and opening the sash like a casement window, or by lifting the latch farther and allowing the window to open at the top, turning it into a hopper window.

Many builders order these windows from European manufacturers, even though the lead times for delivery are typically measured in weeks and the windows are more expensive than what’s available here. Tilt-turn windows also are made by some U.S. companies. Manufacturers point to the versatile operation of the windows, and users often mention how solidly built the windows feel with sash that opens and closes as precisely as a bank vault and multi-point locks that help seal out drafts.

Ben Freed, who launched a window importing company called Mavrik European Windows, says European manufacturers are focused on performance, not necessarily aesthetics. “There is no such thing as a window that is not developed for the purpose of being high performance,” he said in a telephone call. “The main push in the industry is performance. When the new models come out, they’re the next level up in performance. That’s how it works.”

Mavrik’s windows come from Poland, where window manufacturing is fundamentally different than in the U.S. According to Freed, fabricators range from small garage shops to massive factories turning out 5000 windows a month, all of them working with components manufactured by someone else. While there are a few producers that make all their own parts and then assemble the windows, they are “super rare.”

One problem with ordering European windows is the lengthy delay before they get to the job site. Freed says it takes three months to get a window through his company, something that’s unlikely to get much better in the future. That often doesn’t deter builders who specialize in superinsulated houses.

Another problem is that European standards are different than those used by the NFRC to rate performance. So, while it’s simple to convert metric U-factor units to those used in North America, it’s not an apples-to-apples comparison.

“Unfortunately, there isn’t really a direct comparison between a European rating and an NFRC rating,” Urich says. “Changing anything about the simulation conditions —the composition of the light we use to simulate SHGC, interior and exterior temperature conditions, boundary conditions between the surface of the product and the ambient air, and how a spacer is simulated—changes the ratings you’re going to get in any given program. Since one or more of those differences are present when comparing NFRC to any other country, the ratings can’t be compared directly.”

Are European windows really better than those built in the U.S. and Canada?

“It kind of depends on what you mean by superior,” Urich says. “Europeans do take a longer view of their construction, their buildings in general, than we do. So, if you’re buying a window from Europe, especially a higher end window, they are typically built to last for the lifetime of the house, not the 20-year warranty you get from American manufacturers. Not that there’s anything wrong with this, it’s just a different way of looking at things.”

While acknowledging the quality of hardware and materials typical in European windows, Urich took pains not to endorse any particular manufacturer or country of origin. He said buying decisions often come down to the expectations that people have, but cost is certainly a factor.

“You’re not going to recoup a $50,000 investment in windows,” he said. “You’re not going to sell a house based on what kind of windows you have in it. You’re going to sell it based on a floor plan and the price, and whether or not the kitchen looks nice . . . It doesn’t matter if I’m going to save $10,000 over 10 years operating my house if I can’t afford to move into it in the first place. That’s an issue.”

Freed says that on a relatively large custom home with 700 or 800 sq. ft. of windows, white PVC windows would cost between $40 and $45 per sq. ft. delivered. On a smaller project, prices might be in the $55 per sq. ft. range. By contrast, a 3 ft. by 5 ft., bare-bones vinyl window from a big-box store costs less than $200, or a little over $13 per sq. ft.

Long lead times, wider window frames than U.S. buyers are used to, and higher costs probably limit the market for European windows, but they have found a certain niche. “High-end architectural projects are more and more going to European windows because there’s nothing even close in comparison,” Freed said. But, he added, “They’re not a good fit for the cookie cutter 3 ft. by 5 ft., 3 ft. by 5 ft. window setup. It’s a fail. It’s not a good use of the product.”

Calculating energy savings

Better resistance to condensation and higher comfort are good reasons to invest in better windows, and lower energy costs are another plus. The Efficient Windows Collaborative, which is now part of the NFRC, allows users to estimate energy savings with an interactive cost calculator on its website.

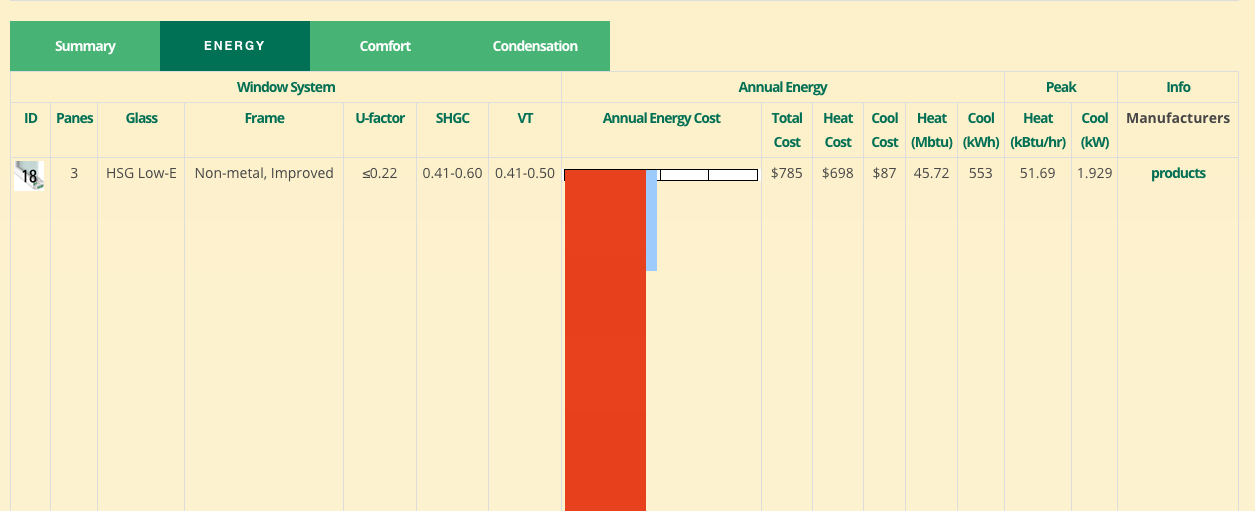

The program covers both new construction and retrofits. After plugging in a number of variables for new construction—such as window orientation, house location, and house shape—you can scroll down through a number of window choices and see estimates on annual heating and cooling costs.

In one scenario for Portland, Maine, choosing triple-pane units with a U-factor of 0.22 or lower and a SHGC of between 0.41 and 0.60 yielded the best results of available options: total annual energy costs of $785. Energy costs gradually increased as window features changed, peaking at $1552 for single-pane units with clear glass and a metal frame (a U-factor of 1 or greater).

For each type of window, the website also provides the names of manufacturers and links to their websites. The best-case windows for Portland, for instance, are made by Fibertec Window & Door Manufacturing and Great Lakes Window, and the website lists available products, by name, making a followup with the company for pricing and availability much simpler than if you were starting from scratch.

Is the investment cost effective?

The return on investing in high-end windows was part of a paper on net-zero construction written by Gary Proskiw, a professional engineer from Canada, a decade ago. Proskiw weighed the cost of installing an extra south-facing window for increased solar gain (and reduced heating costs) versus the savings that a homeowner might expect to see. The new window measured 1 sq. m. and cost $318 more than an equivalent area of insulated wall. Keeping in mind that the numbers are somewhat dated, Proskiw calculated that the investment would reduce energy consumption by 19 kWh per year, which was worth $1.90 at the time. It would take 167 years for the investment to pay for itself in reduced energy use.

Martin Holladay reported on Proskiw’s work in this GBA article in 2011. At the time, he also spoke with Rosenbaum, who told him that adding an extra south-facing window 1 sq. m. in size on one of his house designs on Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, would save 120 kWh of energy a year. If the window could be installed for the same incremental cost as the one that Proskiw used in his calculations, the simple payback would be 26 years.

After running the numbers on the extra south-facing window and coming up with a simple payback of 167 years, Proskiw wrote, “Given that the life expectancy of an Insulated Glazed Unit (IGU) is about 25 years, it is clear that the inclusion of the extra [sq. m.] of south-facing window area can never be economically justified.”

Proskiw also looked at the economics of upgrading a 1-sq.-m. window from a relatively conventional triple-glazed unit to a more energy-efficient model that used low-e glazing and argon gas fill. The added cost at the time was $128, and the better quality window would save 8 kWh of energy a year, which was worth 80 cents. He estimated the payback at 160 years.

It’s important to remember that Proskiw’s research concerned net-zero energy houses in Canada. The economics could be different in conventional construction:

“These results may appear surprising,” he said, “but they are very consistent with our understanding of the behaviour of net-zero-energy (NZE) housing. The reason the two window upgrades fared so poorly from an economic perspective is that the space heating load in a NZE house is very small compared to any other type of house. By adding window area, or upgrading window performance, the space heating load is reduced but it is already so small that there is little opportunity for further savings. Had these two upgrades been applied to a conventional house with a much larger space heating load, the energy savings would have been significantly larger and the economics much more favorable.”

What designers and builders say

If “high performance” is a relative term, what does it mean to builders and designers who routinely work on projects that would require them?

“I would say that a high-performance window is, at minimum, one that performs significantly better than the building code requires for U-factor, and that it maintains airtightness better than typical windows,” Michael Maines, a Maine-based designer and builder, said in an email.

“What U-factor is appropriate depends on the project,” he continued. “The 2018 IRC requires a maximum U-0.30 for windows in Climate Zones 4-8. In Climate Zone 4, a high-performance window might be U-0.25. Here in Climate Zone 6, it might be U-0.20. In Zone 8, I wouldn’t want anything less than the best available window performance, at about U-0.11.”

Maines points out that there are no specific requirements for airtightness. Windows that close against a gasket (like a casement) should generally perform better than one with sliding sash, but that’s not always the case. One project Maines worked on had good quality double-hung windows, and the house tested better than the Passive House requirement (0.4 air changes per hour at 50 pascals of pressure). “So, they can seal well, at least initially,” Maines said, “but it depends on the window details.”

Brands that Maines has used include Makrowin, Schüco, Pinnacle Window Solutions, Sierra Pacific, Marvin, and, just recently, Mathews Brothers.

Eric Whetzel, an owner/builder who detailed the construction of his high-performance home outside Chicago in a GBA blog called “Urban Rustic,” looked at several window lines before making a decision. “When we were shopping for Passive House windows back in 2016, it didn’t seem like there were too many options at that time,” Whetzel said in an email. “If I remember correctly, we considered Zola, Intus, Klearwall, and Unilux. We ended up going with Unilux. The main specs we were looking for were overall R-value for the windows (including frames), U-value for the glass, and air leakage.”

One factor in Whetzel’s case was his desire to use a type of glass called Suntuitive, which Unilux had handled in the past. Customer service is a key consideration. “Even if you have past experience with some of these companies (either as a builder, designer, or architect), it can’t hurt to look around online for recent reviews,” he wrote. “As companies grow or change management, it’s not uncommon for customer service or product quality to suffer.” You can read more about Whetzel’s selection process here.

In Newfoundland, Canada, David Goodyear chose a nearby manufacturer when he built his house a few years ago, opting for triple-glazed Kohltech “Energlas” windows on the recommendation of his Passive House consultant. The windows are manufactured in neighboring Nova Scotia and are available in the U.S. as well as Canada. “After reviewing their U-values, performance based on the PH model, and in the light of transportation distances, I felt it was the right choice,” Goodyear wrote. “Our local market is pretty slow on performance windows but we do have a Kohltech dealer. Having a local dealer did help finalize the decision, as it would make things like warranty issues easier if inspections had to be arranged.” Overall, he’s been pleased. (Goodyear wrote about the project in a series of blogs at GBA called “Flatrock Passive.”)

In a milder climate, high performance can take on a different meaning. High-quality construction, good support from the manufacturer, and a strong warranty all are near the top of the list for Armando Cobo, a Texas-based designer of net-zero-energy homes. Those triple-glazed European tilt-turns? Not so much.

“I like to be pragmatic,” he said in a telephone call. “I understand that in northern climates, a high-performance window is a lot more important than it is for us down in the South. Here, in Climate Zone 3, I will probably never specify a triple-pane window. It doesn’t make economic sense at this point. We get away with the stuff that people in New England don’t get away with. It’s good to be pragmatic and specify quality, high-performance windows but without also having to go to an extreme and break the bank.”

Told that a European window might cost $55 per sq. ft., Cobo replied, “You know I get it. There are certain people that like to drive Ferraris, but I think having a Cadillac is good enough. I think driving a Mercedes or a Lexus is good enough too. I don’t have to drive a Bughatti or a Rolls Royce to get my kicks.”

Originally published on GreenBuildingAdvisor.com.