Bay Windows That Belong

A simple technique for determining a good shape for a bay window is to match the proportions of the facade on which it sits.

My clients typically don’t request bay windows at the onset of a project, but they often ask for interior spaces with window seats, lots of light, and extra space. Similarly, they ask for attention grabbing bump-outs and exteriors with charming details. All of these wishes can be satisfied with a bay window. The tricky part is designing one that looks like it belongs.

Not all bay windows are the same

The term bay window is used most often to generalize a category of window that projects from an exterior wall. If you want to identify such windows more accurately, however, you need to know the differences between the common types of bay windows.

An oriel is a bay window that is not supported by a foundation, but rather with an angled or molded base or with brackets. Traditionally, oriels were used on the upper floors of a house; over the past half-century, they have become common on first floors as well. Like other bay windows, oriels generally look best when the roof slope is minimal—1⁄4 in. per ft. to a 3-in-12 pitch at most.

A box bay has sides that are square to the walls of the house. The sides may include windows, but often, the windows are reserved for the primary face only. Box bays are ideal for integral window seats because the square sides create a natural backrest. Bay-window kits, including ones for box bays, are available with hardware that makes support from below unnecessary. However, box bays in particular always look odd without visual support from below. I think that box bays look best when they do not project too far from the exterior wall—15 in. at most—so that they don’t appear too massive.

A bow window is a bay window with a curved face. Although units with curved glazing are available, a much more common approach is to create the appearance of a curve with four or more facets. For a bow window to appear natural on a house, the roof slope should be minimal and the underside supported visually.

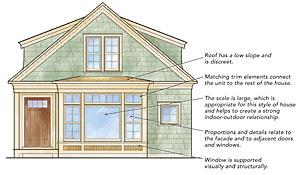

Horizontally proportioned houses

A simple technique for determining a good shape for a bay window is to match the proportions of the facade on which it sits. A horizontally proportioned facade will look good with a relatively long, squat bay window. A bay window on a horizontally proportioned house might have broader overhangs on the roof and wider windows in relation to their height. Panels below the windows may be squat or even eliminated in favor of brackets or corbels. The bay should not project too far from the house, and if the sides are angled, then the angle should be fairly flat—certainly less than 45°, and more in the range of 15° to 30°.

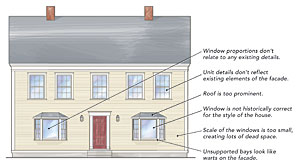

Not all houses accommodate bay windows

Bay windows are particularly well suited to Italianate, Queen Anne, shingle-style, cottage-style, and Craftsman-style houses, and contemporary houses derived from these styles. They are not appropriate on original or reproduction Cape Cod or other colonial-era houses. I cringe when I see bay windows tacked onto the side of an otherwise stately old colonial. They never would have been included in the original construction of the house, so they always look like an awkward afterthought. That’s not to say that they can’t be added successfully to more contemporary Capes and colonials from the mid-1900s onward, but they need to reflect the style and detailing of the house.

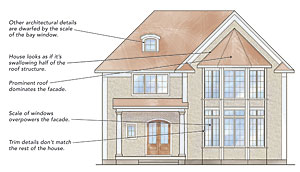

Vertically Proportioned Houses

Bay windows usually work well on vertically proportioned houses. Just look at almost any Queen Anne-style house, such as the Painted Ladies of San Francisco. A vertically proportioned house will benefit from a tall, narrow bay with a similar aspect ratio. To determine the correct aspect ratio when sizing a bay window, draw a line from the lower corner of the exterior wall on which it will be located to the opposite upper corner. Then draw a rectangle or square to denote the bay window, making sure that the corners of the bay window fit onto that line.

Be careful of the window’s roofline. You may think that extending the roof vertically, as if it were a turret, would be a good thing. It’s not, and ends up looking like the house has swallowed half the turret. Keep the roof minimal, or bring the upper house wall forward so that the bay window needs no roof. Be especially careful of visually unsupported bay windows in a vertical composition. If the window is on the first floor, use skirting or a foundation below it; if it’s on an upper level, it should have brackets, corbels, or moldings supporting it, if only for visual effect.

Drawings: Mike Maines