Buying Windows

To make an informed decision, it’s important to understand what's listed on the NFRC label, and what isn't.

While working full time at Fine Homebuilding and doing my best to be an attentive father and husband, I remodeled the home we were living in on nights, weekends, and “vacations,” and on a shoestring budget. In hindsight, I had bitten off more than I could chew. And though I improved the house in a number of ways, with a little more time and money, I could have done better—maybe that’s always the case.

One decision that I don’t regret is my choice in windows. I replaced all but one of the windows on the house with units I bought off the shelf at Home Depot (one large window I had to order). They were all from Andersen’s 400 series—white vinyl-clad exterior with unfinished pine inside. At the time, this was the premium window in stock at my local Home Depot.

I didn’t put a lot of thought into this purchase. After hearing many builders’ positive opinions on Andersen windows as a great value and visiting Andersen’s headquarters for meetings a few times in my role at FHB, I felt good about the company and the product. And while I could say the same thing about Marvin windows, the Andersen units were available when I needed them, ten minutes from home.

This is not how I would advise anyone else looking to buy what can be one of the most expensive product purchases on a project—do a little research, please. I had to do some of that research when I was tasked with the intro presentation for an episode of the BS* + Beer Show. Here is some of what I learned.

Comparing window performance

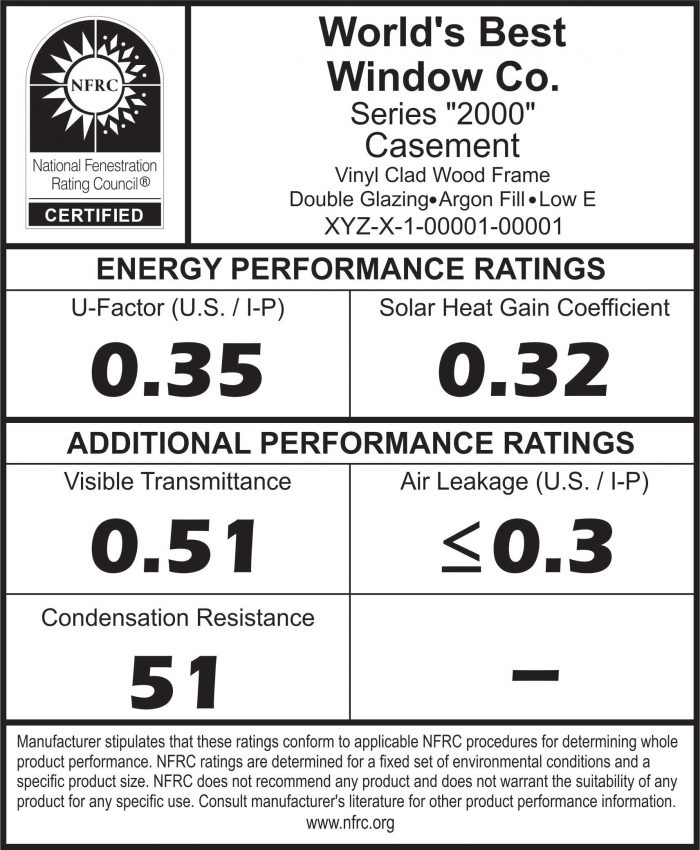

The quickest way to compare the performance of American windows may be checking out the National Fenestration Ratings Council (NFRC) label, or at least the data it contains. On their labels—and on most manufacturers’ websites—you can find a window’s U-factor, solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC), visible transmittance, air leakage, and condensation resistance. While these aren’t the only considerations for choosing a window, and they don’t offer an easy comparison to European windows, they are important performance specs.

The NFRC created the testing procedures for this data, and manufacturers are required to use independent labs to perform the tests. The prescriptive aspects of the International Residential Code (IRC) calls for these ratings to be used, and the labels are meant to be left on the windows until the building has passed inspection. Windows without labels are to be assigned a U-factor, SHGC, and visual transmittance that you can find in the IRC chapter on energy efficiency.

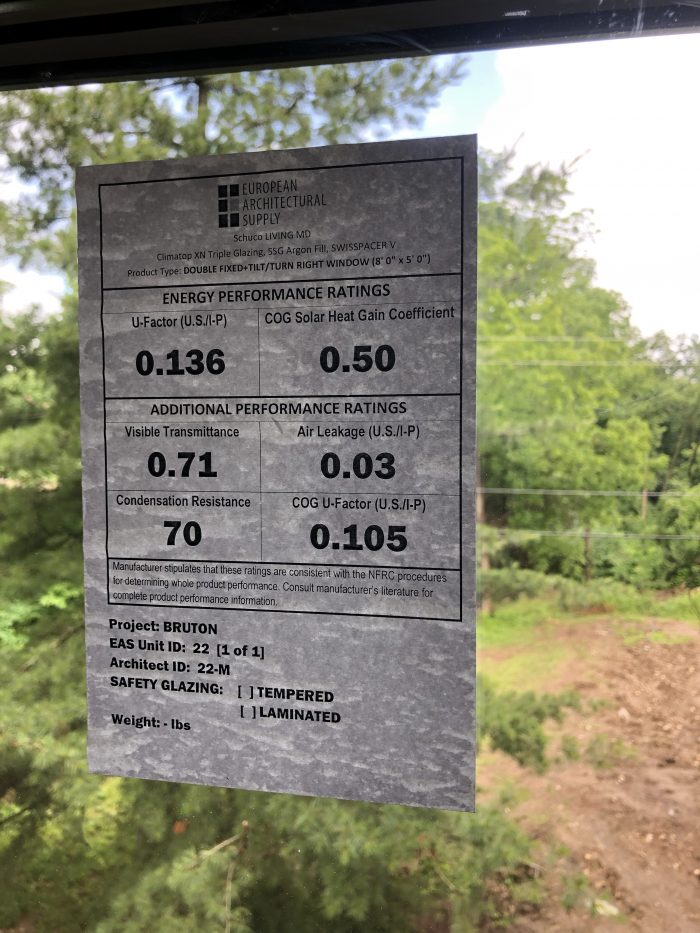

If you choose to use European windows, they won’t have an NRFC label because the NFRC doesn’t operate in Europe. European windows are rated by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). The rating is ISO 10077-2 and while the ratings are reliable, Enrico Bonilauri, co-founder and chief product officer at Emu Building Science says that some of the testing is performed differently than that which is done for the NFRC standard, and some of the ratings are more relevant, in his opinion.

For example, the NFRC tests for U-factor are based on an outdoor temperature of 0˚F. The European outside testing temperature is 36.5˚F. “Because the two ratings have such a different reference condition, one can not really compare apples-to-apples,” Bonilauri wrote in an email. “It’s like testing the efficiency of the brakes of a car at significantly different speeds. NFRC has more extreme conditions, say 120 mi/hr. The results are not wrong, per se, just not very relevant to the actual use of the system being tested (e.g. for a car driving at max 75 mph).”

Also, if you choose to use European windows, the labels may not come attached to the glass as they do on domestic windows, Missouri builder Jake Bruton told me. Jake’s never had a problem with building officials when using European windows; and he uses the labels, which are shipped ahead of the windows, as a way to check his order. “In other words, put each sticker on a window as it comes out of the container,” Bruton wrote in an email,” and you should run out of windows and stickers at the same time.”

About the NFRC ratings

Here’s a quick look at what’s on the NFRC label, some thoughts on why these specs are important to consider, and where they fall short.

U-factor: If you are used to thinking in R-values when considering thermal performance, U-factor may take some time to get used to. While R-value is the measure of a material’s resistance to heat transfer, U-factor is the measure of heat conducted through the material. If your good with math, it’s easy: U-factor is the inverse of R-value. Let’s use a U-factor of .40 as an example: 1 / .40 = 2.5 (that’s an inverse equation because 1 / 2.5 = .40). A U-factor of .40 is equal to R-2.5.

If you’re like me and math isn’t your thing, just remember this, unlike R-value, where a higher number means better thermal performance, with U-factor, the lower the number, the better the thermal performance.

The U-factor found on the NFRC label describes whole-window performance. This is an important distinction, particularly because you may find a listed “center-of-glass” U-factor in product literature, but that would not include other components of the window, like the spacers or the frame. Not only could that be misleading when you are choosing a product, it could throw off your energy modeling.

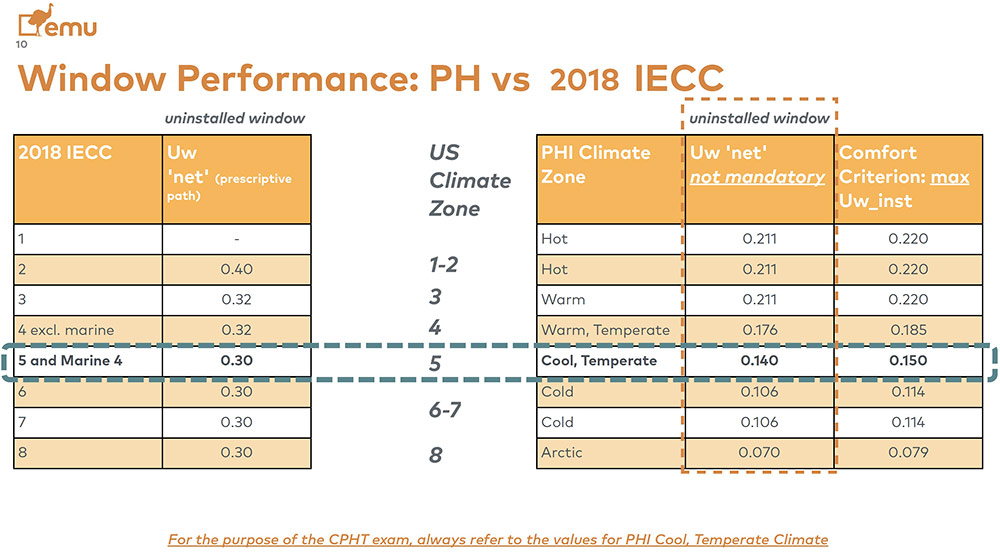

In all climates, a low U-factor is advantageous and high-performance builders often look for windows with much better-than-code specs. That said, here are the prescriptive U-factor requirements for windows by climate zone, as far as the current IRC is concerned (this information can be found in Table N1102.1.2 of the 2018 IRC):

- Climate Zone 1: No requirement for U-factor

- Climate Zone 2: A U-factor of .40 is required

- Climate Zones 3-4: A U-factor of .32 is required

- Climate Zones 5-8 and marine 4: A U-factor of .30 is required

For homeowner comfort, Bonilauri says that U-factors lower than those typically required by codes are needed. “The average temperature on the surface of the window has to be less than 7.6°F below the average temperature of the room.”

In Climate Zone 5, for example, you’ll need a U-factor of 0.140 to meet this requirement. As we just saw, the current energy code allows a much higher U-factor. “The performance is going to be considerably better, but this is really to look at having an even thermal comfort condition inside the building,” says Bonilauri.

Solar heat gain coefficient: A window’s solar heat gain coefficient is a number between 0 and 1 and a measure of the solar energy that will radiate through a window. The lower the number, the less solar energy passes into and heats the home. Like U-factor, the NFRC SHGC rating is for the whole window as various components will transmit solar energy at different rates.

Choosing the right SHGC for a home’s windows is a nuanced decision. While it may be advantageous to keep as much solar heat out of the home in a cooling-dominant climate, in a heating climate, designers and builder count on that energy to help heat the home in the winter. In these situations, a higher SHGC may be chosen and a designer may use shading methods to mitigate solar heat gain in the summer.

“Up here we often want very high solar heat gain,” says Maine-based architect Emily Mottram. “But in Florida or Texas, you’d probably never want heat gain [through your windows].”

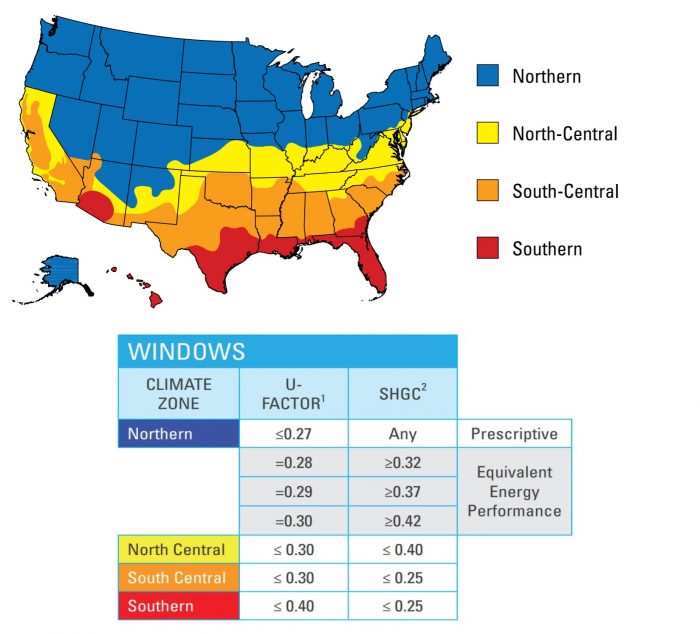

While to IRC has no prescriptive requirements for SHGC in Climate Zones 5 and higher (nor in marine zones), it does require a specific number for the warmer zones (this information is also found in Table N1102.1.2 of the 2018 IRC):

- Climate Zones 1-3: A SHGC of .25 is required

- Climate Zone 4: A SHGC of .45 is required

Another quick way to spot an efficient window is to look for the Energy Star certification which requires that windows meet certain U-factor and SHGC ratings in the four designated climate areas shown below.

Visible transmittance: Another 0 to 1 scale, visual transmittance is the measure of how much visible light gets through a window. Because one of the primary purposes of windows is daylighting, allowing light into the home is important. Also, when windows are used to capture specific views that are important to homeowners, this rating is particularly significant, and a high visible transmittance rating is desirable for a clear view.

Visible transmittance has an aesthetic effect too, as windows that let in less light—a lower number on this scale—may appear darker than window with a higher rating, as if they were tinted. This is one reason why designers are reluctant to use different windows on different elevations of a home, even when it may seem appropriate to do so.

“The hard part about using different performance specs on different parts of the house generally has to do with the visual of the windows,” Says Mottram. “Most people like open-concept plans these days. So if you decide to do a low-e window on the west side of the house to cut down on solar heat gain, and that window is treated with a film, it is going to be a different color than the other windows. It’s not noticeable when all of the windows are the same, they just look clear. So you would only want to use different performance specs in different locations when the windows are not in the same room.”

Air leakage: While this may seem an important statistic to know before purchasing a window, it is an optional rating for manufacturers on the NFRC label, where a lower number means less air leakage. Air leakage is measured in cubic feet per minute per square foot of window area (cfm/ft2), and the NFRC test used to measure air leakage is meant to simulate a 25 MPH wind. For context, both the IRC and Energy Star call for an air leakage rating of ≤ 0.3 for windows.

It’s worth noting the importance of installation here. A poorly installed window can have much greater air leakage through the shim space between the framing and the window frame than through the window itself. This is why Mottram says that windows are one of the last things to update on an existing home. First, take care of air sealing and insulating the building envelope.

Finally, while fixed windows will generally have the lowest air infiltrating ratings, followed by tilt/turn windows, and casement and awning windows that have a locking mechanism to pull the sash tight to the weatherstripping, Mottram says that this is actually one of the less significant air infiltration concerns in a tight house.

“There are ways to get to .6 air changes with double-hung windows,” she said. “The significance of a window has more to do with your comfort and less to do with the performance of a house.” What is really improving the performance of a home is how the window is installed.

Condensation resistance: You won’t find this rating on all windows, as it is another voluntary standard. The range is 1 to 100; the higher the number, the less likely a window is to gather condensation on the glazing.

The test is performed by calculating the likelihood of condensation forming on the interior of the window based on indoor surface temperatures when it is 0°F outside and with various indoor relative humidity levels. In other words, it’s a dew point temperature calculation that is then averaged to get to the rating.

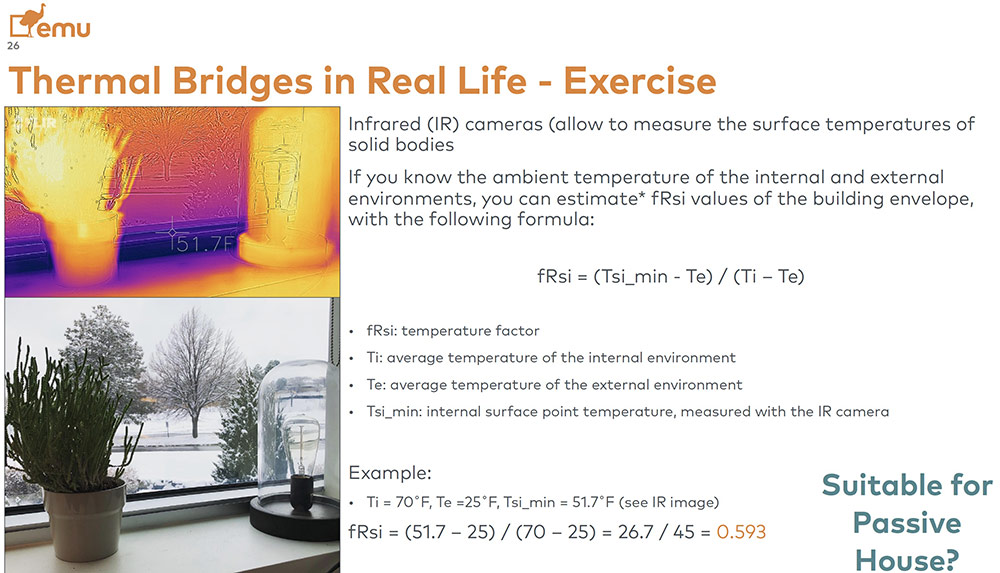

“There are two main values that come with good windows that are not addressed by the energy code nor the NFRC rating, and that is the avoidance of condensation and thermal comfort,” said Bonilauri. “NFRC does have a voluntary rating for condensation resistance, and that is a 0-100 score, but if you dive into the algorithms, it is an average of averages, so it is just a score. In Europe, they look at the temperature factor, which is an assessment of the coldest spot on the window and based on that and based on your climate, you can see if you are going to have condensation.”

Bonilauri recommends looking for this condensation resistance rating and using the values specified by Passive House Institute to choose the right temperature factor rating for your climate zone, which ranges from .55 to .80—from the warmest to coldest North American climates. A few domestic window makers that are now offering this rating include Alpen, Deceunink, Intus, Rangate, Zola, and Wythe.

More considerations and more jargon

The second half of the 20th century was full of innovation and ingenuity on the part of window manufacturers. When you encounter the NFRC sticker, at the very top of the label you’ll find the name of the window manufacturer, the series that the window belongs to, the type of operation, and a bit of information about how it is engineered. Two purchasing decisions that we won’t get too deeply into in this article are operation type and frame material.

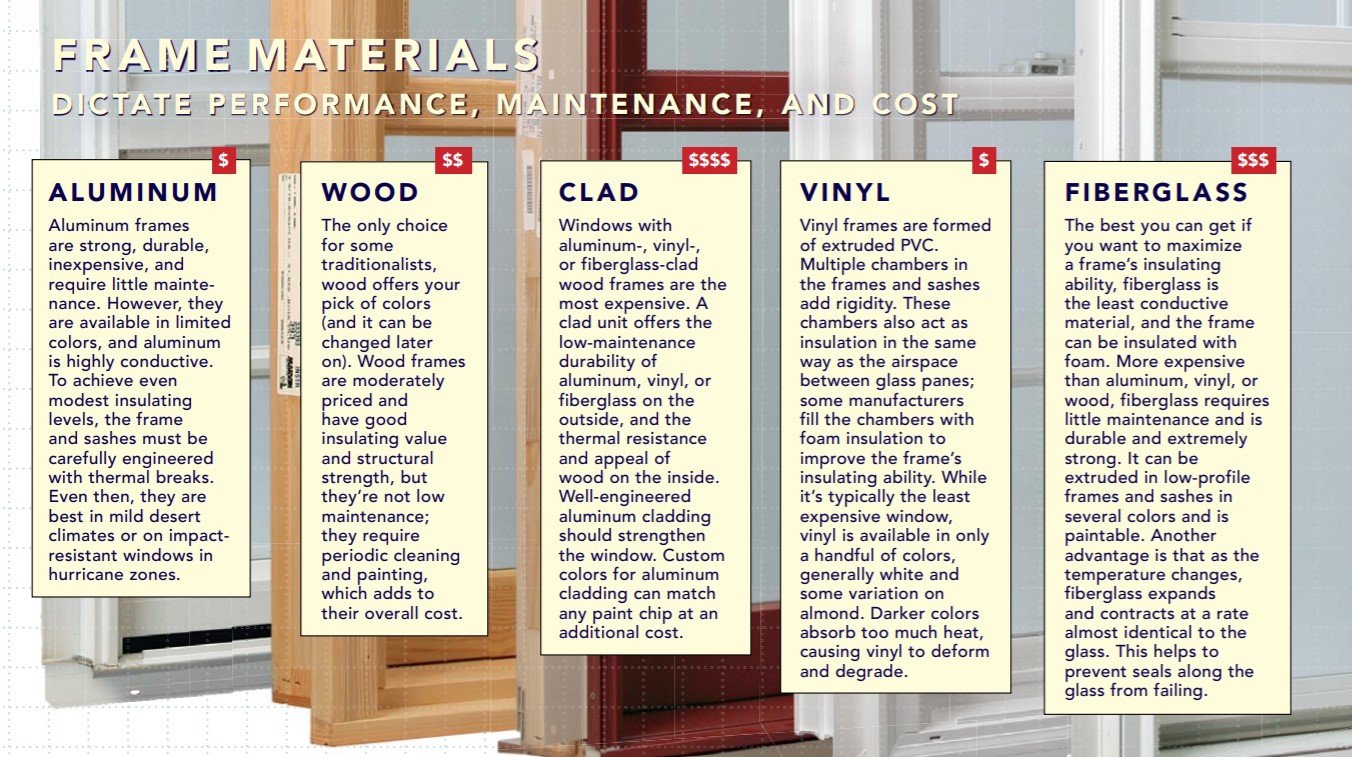

There are definitive pros and cons to fixed windows, double-hung, casements, awnings, sliders, and tilt/turn units that include how well they seal, how well they ventilate, their long-term durability, cost, and at least in the case of tilt/turn windows, how much clear interior space they need to open fully. Still, this choice is often driven by style and homeowners’ comfort. When performance specs are equal, frame material is often a decision based on aesthetics, durability, maintenance, and cost.

Understanding some of what is listed regarding how the windows are engineered launches us into another round of terms to understand, some of which will appear on the NFRC sticker, some of which you may not encounter until you look at a manufacturer’s website or product catalogs.

Insulated glazing unit (IGU): Most modern windows are double- or triple-pane, which means that they can have two or three pieces of glass. Between the glass, the windows are insulated, often with argon, or less commonly krypton gas. This assembly is known as an IGU. Though there are some domestic window manufacturers who make triple-pane windows, the tilt/turn units that you’ll often see on high-performance homes are likely imported from Europe. And though the term triple-pane is often used synonymously with high-performance, that’s not a given. There are many double-pane windows and windows with suspended films available that perform very well and may be just right for your climate.

Warm-edge spacers: The layers of glass in an IGU are separated by a spacer that keeps the insulating gas in and outside air out. Aluminum is a common spacer material, but it is highly conductive. So-called “warm-edge spacers” are made from a variety of materials from foam and other plastics to stainless steel and are less conductive than common metal spacers. Warm-edge spacers can therefore help to yield a higher performance window.

Low-e coating: The “e” stands for emissivity and these super-thin metallic coatings are often applied to the glass layers of an IGU to absorb and slow emissivity of radiant energy. While today, most low-e coatings are applied to one or more of the glass surfaces of double- and triple-pane windows, the technology started with suspended-films (see below). The most effective surface for the low-e coating to be applied to depends on the climate the window will be used in.

Suspended films: To challenge the performance of triple-pane windows without one of their disadvantages—weight—some window manufacturers engineer their IGUs with sheets of polymer between the two glass surfaces. These films can have low-e coatings applied. Heat Mirror is a well-known product used in suspended-film IGUs.

Only as good as the installation

There is at least one more thing that you’ll need to consider when purchasing windows and that is how they install. The two main types of windows for wood-frame construction are flanged (or nail fin) and flangeless (or European) and there are some variations on how each are built and installed.

With the right flashing and air sealing techniques, all windows can be installed well, but it’s worth reiterating the importance of a quality installation for performance, comfort, and durability. In fact, another reason I have no regrets about my window purchase was because the fully-welded nailing flanges on the Andersen windows I chose made me feel confident in my ability to install the windows really well.

Originally published on greenbuildingadvisor.com