How to Install Doors in Thick Walls

Superinsulated walls make it challenging to install standard-size door jambs and sills. Energy-efficient-home designer Michael Maines offers some workable solutions.

Synopsis: When installing doors in buildings with high-performance envelopes, you need to contend with thick walls and other insulation details. Contributing editor Michael Maines describes three approaches to installing doors in thick walls: using doors with thicker jambs, creating a stepped opening, or holding the door to the interior so it can open fully. When situating the sill, you must plan for a deep threshold. Maines details the inclusion of a sill extension, and describes how to create structural support for the extension over exterior insulation or an elevated slab by created a formed recess.

In the last issue, we looked at installing windows in thick-wall assemblies. In this installment, we’ll focus on doors. In high-performance envelopes— those with thick walls and other details that allow for extra insulation and air-sealing—installing standard doors poses challenges that builders don’t typically encounter on more conventional builds. The placement of the door relative to the depth of the opening can affect the swing and the threshold details, and thermal bridging can be an issue. There’s no single solution, but I’ve had luck with the details shown here. They can be adapted to work with imported doors, which are slightly different than what most North American builders are used to, but they’re based on standard door and jamb profiles.

Gauging the swing and setback

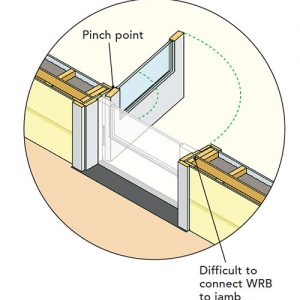

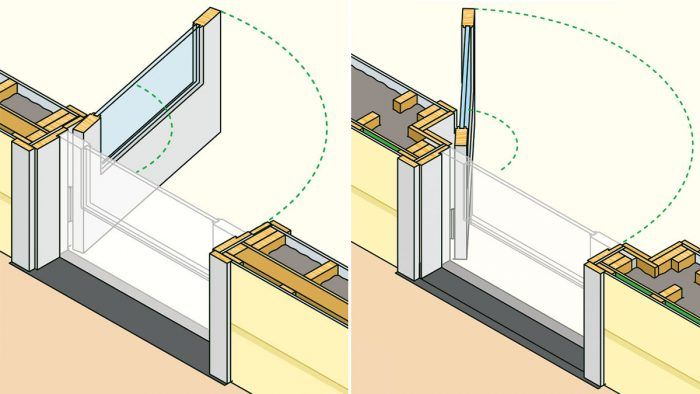

Thick-wall assemblies can affect the degree to which a door opens as well as how easy or difficult it is to tie the water-resistive barrier (WRB) and air barrier into the jamb. Below are three approaches to consider.

Thick-jamb solution

A standard door installed to the exterior makes for simple trim details, but it requires interior extension jambs, which means the door can only open a bit more than 90°. If there’s no perpendicular wall to open against, the door will bind against the trim, which can loosen hinges and damage both door and trim. Plus, the WRB and air barrier are typically at the sheathing, which makes it complicated to tie the door frame into those layers because they will align toward the middle of the door jamb.

Ideally, order a door with thicker jambs. There are 6 9/16-in. jambs available off the shelf—perfect for 2×4 construction with 2 in. of exterior foam—or you can build your own or buy custom for thicker wall assemblies. Locally, I can get builder-grade doors with 9 1/8-in. jambs, and have seen jambs up to 11 1/8 in. from other suppliers. But even those depths are not always enough, and if there’s a rainscreen, the details can get tricky because of the added thickness on the exterior side.

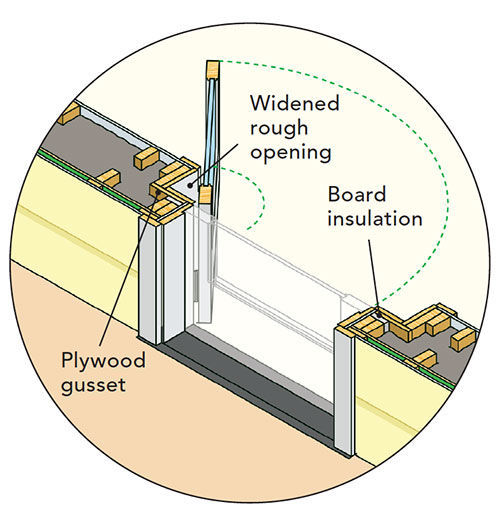

Stepped situation

Another option—especially suited for a double-stud wall— is to create a stepped opening. Make the outer rough opening normal size and the inner opening wider than normal. This won’t enable the door to open a full 180°, but it will significantly increase the opening angle, and you can flare the inner portion for even wider access. A downside is that it reduces the amount of insulation near the door, though you can break the thermal bridge at the framing by adding a layer of rigid-board insulation on the interior side. Adjust the width of the inner rough opening and use a plywood gusset aligned with the wall to tie the two walls together.

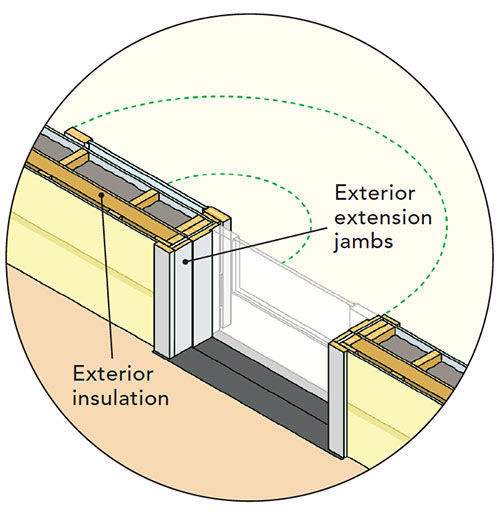

Interior installation

My preferred method is to hold the door to the interior so it can open 180°. When there is continuous exterior insulation, this makes it easy to tie in the WRB and air barrier, provided they are located at the sheathing layer. To do this, use exterior extension jambs and a sill extension of some sort. Continuous exterior insulation is a natural fit for exterior extension jambs and sill extensions, though both require thoughtful and well-executed flashing details.

Situating the sill

A deeply set door calls for an equally deep threshold, which can be achieved by fabricating an aluminum or stone extension. With a concrete-slab foundation, locating the sill where it will get maximum structural support is key.

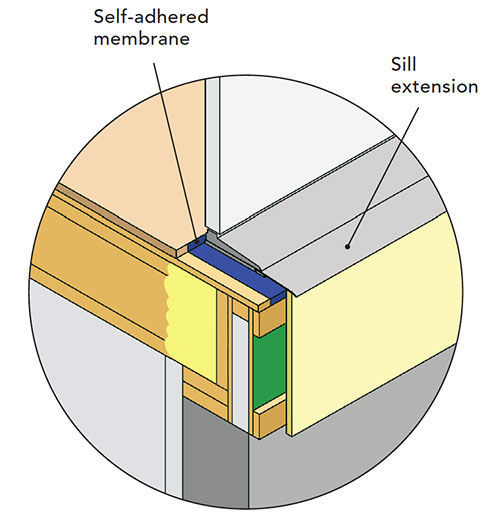

Deep extensions

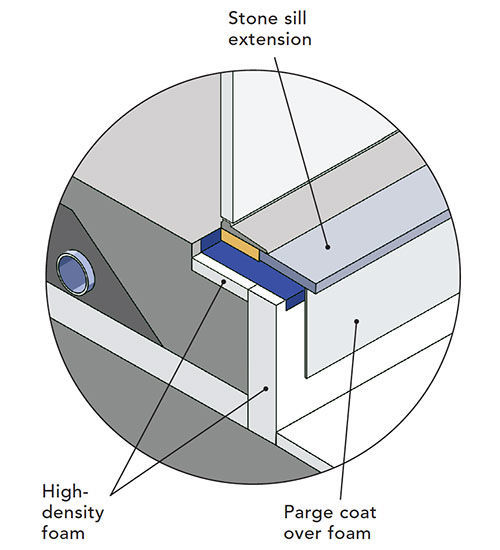

Door sills or thresholds can be a problem in thick walls when you locate the door at the interior side of the wall. If your door manufacturer doesn’t offer an aluminum sill deep enough for the full depth of the wall, you can make an extension using commercial ramp stock—Pemko is a reputable brand. Their ramp stock comes in different shapes and sizes, so you may need to cut any that are too deep—fortunately, aluminum cuts easily on a tablesaw. The sill extension should be sloped to drain to the exterior. You could recess the outer portion of the subfloor assembly, but I think it’s easier in this case to raise the entire door on a 3/8-in. to 1/2-in. shim. Make the shim continuous to meet door-installation requirements. Seal the joint between the factory sill and the sill extension with a high-quality sealant, and be sure to use a self-adhered-membrane sill pan so you don’t get the thermal bridging and condensation at the interior that you would get with a metal pan. The same approach also works well when using European-style doors with narrow sills.

Formed recess

Doors installed on thickened-edge slabs have two main problems: The exterior insulation (required in climate zones 4 and higher) does not provide structural support for a sill extension, and if the door is held to the interior, then there is a significant thermal bridge through the top of the sill into the concrete. One solution is to create a formed recess in the slab under the door location, and fill the recess with high-density foam topped with framing lumber to support the door. Standard 15-psi foam would compress too much for the tight tolerances necessary at doors, but 40-psi foam is stiff enough to prevent excessive deflection. (I use borate-treated EPS because it is insect-resistant and the blowing agents have less environmental impact than those in XPS.) Plan ahead and special-order a sheet.

Use a membrane sill pan with a back dam to cap the foam. For the sill extension, you can use metal, but a nice upgrade that can be more affordable than one might think is stone, either from a local hardscape supplier or from a countertop supplier’s scrapyard. A slightly textured surface is preferable for slip resistance. (In my area, slate and bluestone with naturally cleft surfaces are readily available.) Just set the stone in a sloped bed of mortar to shed water, and add 25-psi foam to the exterior, solidly adhered to the the vertical face of the slab. That will be stiff enough to support the sill extension as long as the extension is continuous and relatively stiff.

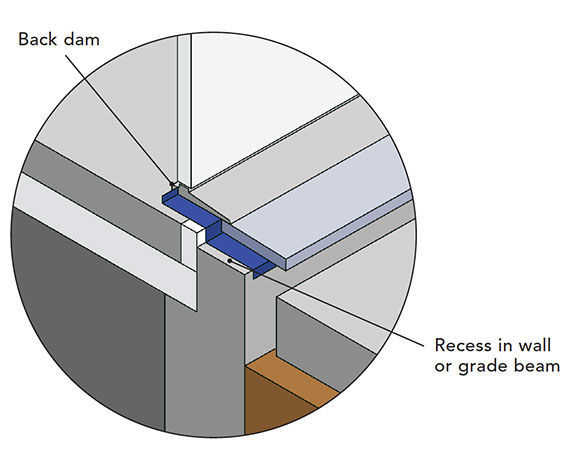

Elevated slab

Similar details work for a raised slab, which is a slab with a frost wall or a grade beam. The perimeter foam at the slab reduces thermal bridging, so there’s less need to form a recess in the slab below the door, but you will need to include a recess in the wall or grade beam. This installation should always include a sill pan, including a back dam (which can be concealed with a small piece of interior trim), because doors are apt to leak in time.

Drawings: Arthur Mount

From Fine Homebuilding #286

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Utility Knife

Nitrile Work Gloves

Foam Gun