Glass in Wet Spaces

Code expert Glenn Mathewson explains the requirements for glazing to protect occupants from injury in slippery locations.

Synopsis: Glass has the potential to cause injury, but the probability of a human coming into dangerous contact with glass is only likely under certain conditions. The International Residential Code identifies a list of places, called “hazardous locations,” where a home occupant is more likely to fall and hurt themselves if glass is nearby. Code expert Glenn Mathewson describes the code requirements for glazing near certain features such as bathtubs, showers, and swimming pools, and warns against interpretations of the code that don’t follow the intent and purpose of the rules.

One night, my dog decided to splash his feet in his water bowl and spilled it on my kitchen floor. During a dark walk for a midnight snack, the reduced friction on the tile coupled with the pull of gravity quickly brought me down. The hazard that caused my fall—wet tile in a dark room—was well within the realm of possibility, but not necessarily probable.

Here’s why I bring up “possible” vs. “probable”: The probable hazards in the built environment—those identified through statistics, science, and anticipated human behaviors— are what building codes aim to protect us from. They aren’t written to protect us from every humanly possible scenario, such as my dog bowl experience, just the probable ones that could result in serious injury.

While there are special rules to reduce falls on stairs, ramps, and walking surfaces over 30 in. high, when it comes to level floors, codes care less about preventing falls than about what you might hit while falling. It would be relatively easy to reduce the probability of slipping and falling by requiring that floors have nonslip surfaces—something like wall-to-wall carpeting throughout houses. But that would tip the balance of freedom and safety that the code aims to maintain. So instead, in places where slips and falls are more likely, the code focuses on making sure you don’t hit anything that might maim or kill you on the way down—specifically “glazing,” a fancy term for glass.

Glass has the potential to cause injury, but the probability of a human coming into contact with it is only likely under certain conditions. The code identifies a number of places where this is likely as “hazardous locations” in Section R308.4 of the IRC. One part of this section— 308.4.5, Glazing and wet surfaces—specifically identifies areas that are expected to get wet and have glass nearby as “hazardous locations.”

“The possibility of a slip and fall in or around any of these features is high, but that possibility alone isn’t the problem; it’s having glass nearby.”

The code identifies certain features where these hazardous locations exist, including hot tubs, spas, whirlpools, saunas, steam rooms, bathtubs, showers, and swimming pools. The possibility of a slip and fall in or around any of these features is high, but that possibility alone isn’t the problem; it’s having glass nearby that turns these areas into hazardous locations.

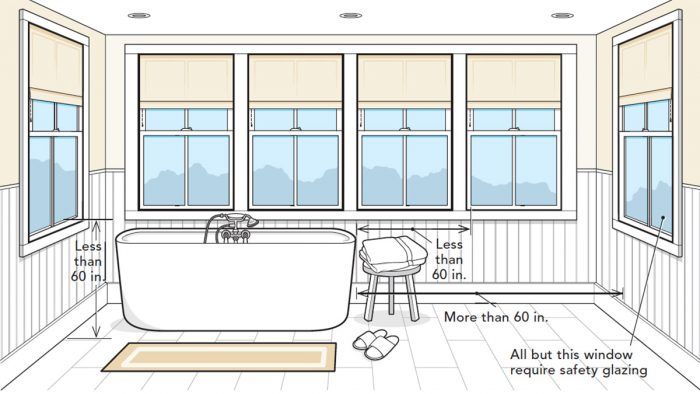

A slippery bathroom floor can send us sprawling, thus any glazing less than 60 in. above one of these wet walking or standing surfaces creates a “hazardous location.” Unfortunately, the code doesn’t read quite as clearly as that. Many code readers are thrown off by the use of the word “edge” in the following statement: “…where the bottom exposed edge of the glazing is less than 60 inches….” Though “edge” sounds something like the exposed edge of a car window that’s rolled down halfway, it’s simply referring to the lowest visible portion of the glass. You would only need to measure up to that, not the portion tucked inside the frame.

This provision obviously applies to glass enclosing or next to a shower or bath, but because we’re likely to drip water on the floor as we step out of or walk away from these features, the hazardous location also extends a bit beyond their boundaries. Only when glazing is more than 60 in., measured horizontally in a straight line, from the “water’s edge” of basin-type features or from the edge of showers, saunas, and steam rooms, does it cease to be considered as occupying a hazardous location. To understand why this is, we turn back to the concept of probable vs. possible. It’s possible you won’t dry yourself off immediately after bathing, but it’s not typical human behavior. For the majority of folks who step out of the tub and dry themselves off right away, the code is designed for you.

The text of Section 308.4.5 in the 2018 IRC is pretty slim, and it attempts to describe what I’ve just explained using a fraction of the words— unfortunately, it’s inconsistently interpreted in the field. What you’ve read thus far is an interpretation of the intent and purpose of this provision, but a word in the very first sentence in the section could lead to an interpretation that would allow a code-approved hazard: “Glazing in walls, enclosures or fences containing or facing hot tubs, spas….”

The current use of the term “facing” in regards to glass near tubs and other wet features can leave some windows shown in the illustration to the right outside of this requirement simply because they are parallel to the tub; they face the area outside of the tub, but not the tub itself. This allows for code interpretations that leave occupants unprotected from those adjacent glass panes. This isn’t how the code was meant to be interpreted, and a proposal for the 2021 IRC was approved in 2019 that will strike the term “facing” and replace it with “adjacent to.” This subtle change should clarify the hazard, and it’s prudent to use the language of this new revision as the basis for interpreting previous editions. The intent and purpose of the rule hasn’t changed, only how it is presented.

Windows aren’t the only concern when it comes to glass; the hazard can also exist with mirrors, which are another form of glazing. However, provided the mirror is continuously backed (attached to a wall), it gets an exception and is no longer considered as occupying a hazardous location. Glass-block masonry units installed according to code are another exception to the provision.

Once you have confirmed that glazing is located in a hazardous location, the IRC requires it be safety-glazed. Nowhere in the IRC is tempered glass required, and it’s typically an innocent mistake when a building authority says that it is. Though tempered glass is the industry norm to address safety glazing in these hazardous locations, an industry norm and a minimum code requirement should not be confused.

What is required is a product that complies with either one of two test standards: CPSC 16 CFR 1201 Category II or ANSI Z97.1 Class A. In brief summary, these standards require safety glazing to be able to take a swinging blow from a 100-lb. weight at the end of a 5-ft. pendulum lifted 48 in. and released either without collapsing, or by collapsing into small pieces. Tempered glass satisfies this requirement by shattering into bits of glass small and light enough to reduce the likelihood of serious injury. However, there are also film products that meet the test standards by keeping standard glass from falling to pieces if it breaks. When tested and proven, these products are just as code compliant as tempered glass.

Identification of safety glazing is critical for installers and building authorities to be sure the proper product has been installed, and tempered glass makes this easy through the use of an etched “manufacturer designation” on the corner of the glass pane. The hard part is simply locating the mark. For the film materials, things get a little tricky, but the code provides a path for verification and compliance.

Section 308.1 of the IRC provides a lengthy description of acceptable identification methods, including the use of a “certificate, affidavit, or other evidence,” but only when “approved” by the building official (defined as “acceptable to the building official”). When films are intended for use as safety glazing, it’s important the installer or designer understand that though this is a code- compliant path, the local building authority may be unfamiliar with it. Communication is never a bad idea, and should be done in advance of choosing one of these products.

There’s a lot more to wet locations and safety glazing than can be presented in a couple pages, so a review of IRC section R308 is the next wise move if you want to learn more about glazing requirements in general. There are more hazardous locations in a home than you might be aware of.

Glenn Mathewson is a consultant and educator with buildingcodecollege.com.

Drawing: Kate Francis

From Fine Homebuilding #295