Laminated Custom Interior Doors

Carpenter Chris Green made interior doors for his own house using a vacuum press.

I’m in the process of a massive renovation. For a builder like me, that’s usually good news, but it’s my own house, which I’m working on between other jobs. An addition and a radical rearrangement of the existing floor plan are nearly complete, but it turned out I needed 10 interior doors. I wanted them to be made of white oak in a Craftsman style. After searching locally, the closest I could come to my ideal was a unit in red oak that wasn’t quite what I had in mind. Also, at $670 each, they were a budget buster.

I’m in the process of a massive renovation. For a builder like me, that’s usually good news, but it’s my own house, which I’m working on between other jobs. An addition and a radical rearrangement of the existing floor plan are nearly complete, but it turned out I needed 10 interior doors. I wanted them to be made of white oak in a Craftsman style. After searching locally, the closest I could come to my ideal was a unit in red oak that wasn’t quite what I had in mind. Also, at $670 each, they were a budget buster.

I’d been thinking about making laminated interior doors for some time. The benefits were that I could choose the individual boards, bookmatched if I pleased, and control the design. So I decided to make my own. I didn’t want to build mortise-and-tenon doors, figuring it would take too long to get up to speed.

Instead, I decided to laminate three layers of solid wood to form a frame and add finish-grade plywood or glass as panels. The rails’ middle layer would extend through the stiles like a built-up bridle joint—strong, flat, and less likely to move seasonally. Gluing and clamping a project like this isn’t for the faint of heart. A completely flat door is essential.

It all came together one day when a friend at the local hardwood mill mentioned a vacuum press. I couldn’t stop thinking about it. It would give me substantial, perfectly even clamping pressure with a finished product as flat as the form it was in. It seemed perfect for making laminated doors.

I built the form and used a compressor and vacuum bag to clamp the entire assembly. That way, once I had finished the setup, I could replicate the remaining nine frames easily.

From the first door, they’ve turned out even better than I imagined—flat, square, and good-looking. The best part was the cost. With the pump, the bag, and the materials factored in, the total cost of each door was about $200. Now I know I can offer custom doors to my customers and make money, too.

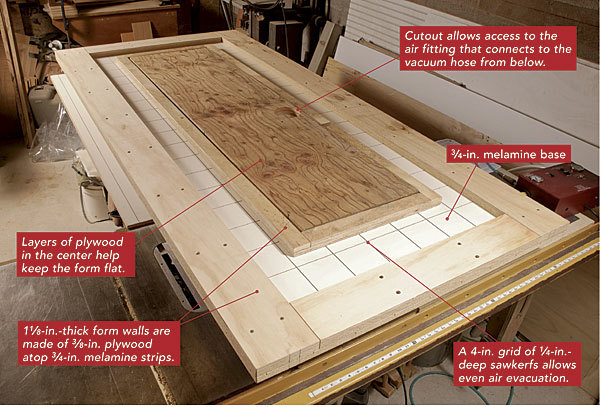

Start With a Ventilated Form

Alternating Laminations Add Strength

The door is made of three laminations of stiles and rails that overlap at the corners to create bridle joints. Each lamination was about 13⁄32 in. thick. Each door was 1-1⁄4 in. thick, 80-1⁄4 in. long, and 30-1⁄4 in. wide. The stiles and upper rail measure 4-3⁄8 in. wide, and the bottom rail measures 6-1⁄4 in. wide.

|

|

| Add the second and third layers of the door frame. Mix up a batch of two-part epoxy (used for its longer open time), and coat the second layer of rails and stiles. Place them glue side down in the form. Repeat with the third layer. |

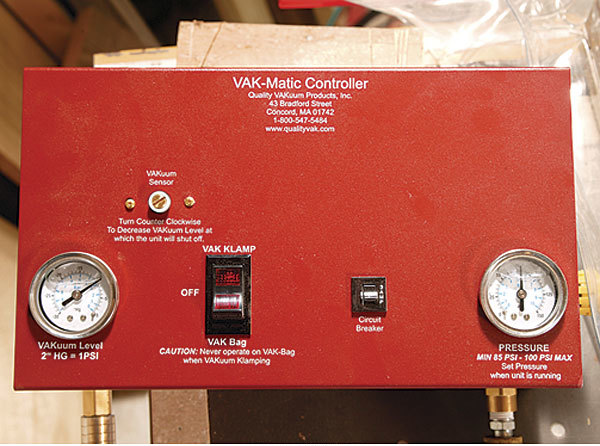

Tool of the Trade

The centerpieces of the process are, of course, the vacuum compressor and bag. There are many to choose from, but after doing some research, I bought the Pro VM4, a 2-hp model from Quality Vakuum Products (www.qualityvak.com) for $570. Sold as a kit, the unit comes with a hose, a fitting, and a 78-in. by 52-in. 30-mil vinyl bag. (The company also offers custom bag sizes up to 12 ft. by 80 ft.) The compressor is a bit noisy, but once it attains the designated pressure, it shuts off and cycles on only to tune up the vacuum.

|

|

| In the bag. The vacuum bag is gradually slid over the form, which is now supported off the table by four 4-in.-sq. blocks, which are removed and then replaced as the bag passes by. When the bag has enveloped the form, the air fitting is pushed through the bag, and the blocks are removed so that the form rests on the table. (A cutout in the table allows access to the air fitting.) The bag is sealed by folding over the open end and applying the bag clamp. Now the vacuum hose can be connected to the air fitting. |

Let the Epoxy Cure for 24 Hours

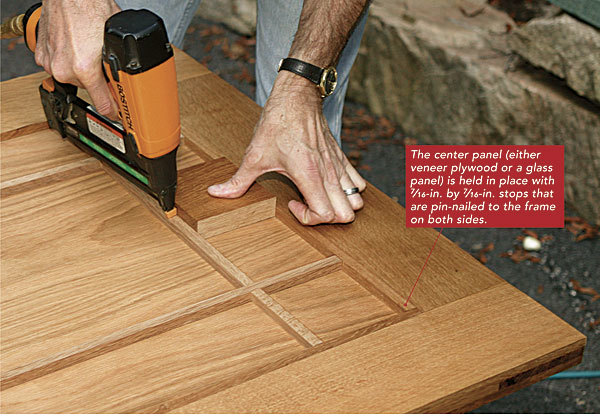

After the epoxy has cured, remove a section of the form, and pop out the door with a flat bar. Next, apply stops inside the stiles and rails to anchor the center panel.

|

|

|

|

| A gauge block speeds layout. A muntin pattern finished the door. The author used an appropriately sized block to position the muntins as he tacked them in place. |

Photos: Charles Bickford