A Bad Splice Might Indicate More Problems

A licensed electrician diagnoses potential problems and explains how to redo the splice correctly.

Q:

I recently discovered burning in the breaker panel from a pair of wires feeding a freezer and a refrigerator. The wires were held together by a yellow wire nut, but not twisted together. The insulation was burned back a couple of inches, and the nut was almost gone. There was no evidence of the wires’ shorting against the metal breaker panel, so I suspect that starting the two motors occasionally but simultaneously somehow caused this.

I respliced the burned wire, and everything seems fine. Should I be concerned?

Reiner Decher, via email, None

A:

Clifford A. Popejoy, a licensed electrical contractor in Sacramento, Calif., replies: Your suspicion is correct: The occasional simultaneous startup of the two appliance motors drew a lot of power, and it caused extreme heating at the bad splice where the two wires were connected. While it’s prudent to check the breaker size and condition, the failure was probably due to an arcing fault at the splice. With the wires held together loosely by the wire nut, the area of contact between the wires was small, causing a point of high resistance: a bottleneck for the flow of energy. When current passes through a point of resistance, a tremendous amount of heat is generated. That’s what melted the insulation and the wire nut.

A motor starting up requires several times the current needed to keep it running. A motor starting under a load, like a refrigerant compressor, requires even more energy. The repeated current spikes eventually caused the failure of what was a marginal splice to begin with. This situation reinforces the wisdom of the National Electrical Code requirement that every line-voltage splice be made in an electrical box that’s accessible without disturbing the finished surface of the building. An accessible box will contain the heat and arc, and allow inspection of the wiring.

And yes, there is some cause for concern; there might be other bad splices. Although a poorly made splice in a less heavily loaded circuit might not develop into an arcing fault, I recommend inspecting splices in heavily loaded circuits (kitchen, washing machine, circuits used to power the vacuum cleaner). If there are other bad splices, check all the wiring, and redo any bad or marginal splices.

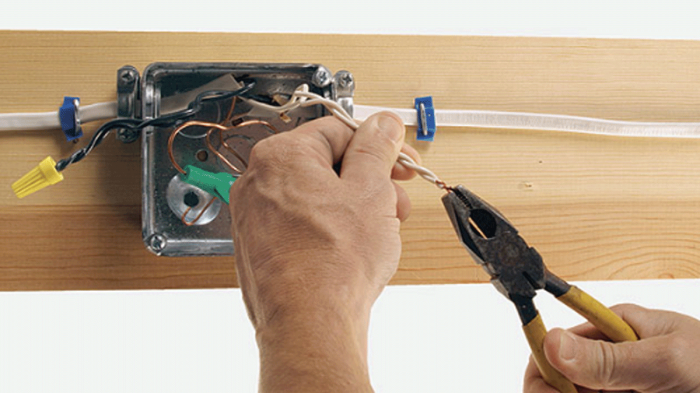

Doing away with this safety hazard can be as easy as redoing the splice correctly. The wires in a properly made splice should be twisted together in the wire nut and have at least two twists in the insulated wire below the wire nut. The twists can be made either with lineman’s pliers, before spinning on the wire nut, or by the wire nut itself. A wire-nut driver, such as the 3M ($17; www.rshughes.com) or one of the Ideal Industries screwdrivers with a wire-nut driver in the handle ($11; featured in “What’s the Best Multibit Screwdriver?”), makes the latter method fast and easy.

Twist first, then cover. To ensure a good connection in a wire splice, twist the wires together with lineman’s pliers before screwing on a wire nut. The wires should be twisted at least two revolutions below the nut, as seen on the black wire.Daniel S. Morrison

Keep in mind that even with a good splice, the load from the appliances must be less than the circuitry capacity. Take a look at the appliance nameplates to find the load of each in amperes. Determine whether there are other loads on the circuit. Total all the loads, and compare that to the breaker rating. Code requires that circuitry capacity exceed load by 20% if continuous loads (defined as those on for more than three hours) will run on the circuit. Not many loads in a house are considered continuous, but I like to allow a 20% cushion anyway.

From Fine Homebuilding #192