At first glance, this didn’t appear to be a complex roof at all – just a simple gable over a small rectangular room addition. Built in the craftsman style, ‘tho, it contained a massive amount of lumber. The ridge alone must have weighed 500 pounds – it took a crane to set it in place! And some complications arose that had to be solved in the field. It was a project that would showcase my craftsmanship, and test my problem-solving skills.

In terms of craftsmanship, one of the primary issues was the all those exposed beams, corble braces, and rafter tails. All that exposed woodwork was thoroughly sanded and pre-painted prior to assembly. Each piece of wood was carefully studied so that its most visible side was the most attractive side. Every joint that would be exposed had to be tight, so that it fit together just like it grew that way. Lag bolts were countersunk. Out of respect for the craftsman style, sloppy workmanship had no place on this project.

While not specifically called for on the blueprints, a gable end vent was clearly in order for in our hot, dry Southern California climate. The existing structure had an off-the-shelf vent that matched the slope of the roof, but looked awkward behind the craftsman style truss bracing that obstructed it. So I designed and site-fabricated some custom gable vents, to fit between the truss bracing on the gable end, involving numerous compound angles. The end result was efficient, attractive, and harmonious with the craftsman aesthetic. I felt justified when a later tour of Greene and Greene’s masterpiece Gamble House in Pasadena revealed a remarkably similar gable vent.

In terms of problem-solving, there were two big issues that had to be dealt with. First involving the support of the ridge beam and a portion of the roof of the existing structure, and secondly, involving a cantilevered beam (off a corner of the building) that carried a hefty portion of roof. Neither had been addressed adequately on the plans.

A massive glue-lam ridge beam was specified on the blueprints. At the gable end, it was bearing on the 2×6 exterior wall of the addition, which was more than up to the task. But on the other end, where the addition tied into the existing structure, the architect had specified…nothing! I met with him prior to construction, and suggested an engineer review that aspect of his design.

His response was to inform me that no engineering was required on an addition of this size – end of conversation! So I was on my own there. I added a glue-lam beam, to carry the other end of the ridge beam, and to carry that portion of the existing roof that bore on the wall section being removed. I also created a triangular “truss” of framing members through-bolted together, to create a strong mid-roof brace. And purlin bracing, with kickers down every 4 feet to a bearing wall, along the entire length of the roof. I like to sleep at night without worrying about my work falling apart, so all was assembled and braced with “overkill” as my guiding principle.

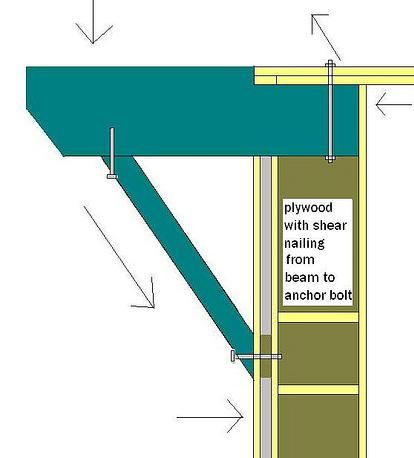

The cantilevered beam at the corner was another issue. Once construction began, I stood on the beam at the corner, and it was very obvious that my roof had an achille’s tendon – the corble brace supporting it, in itself would not be enough. I wrestled with the dilemna, and finally devised a solution involving metal straps, through bolts, and plywood shear panel, all of which would serve to anchor the end where the uplift wanted to occur…all the way down to the anchor bolt in the bottom plate.

In addition, a large section of stuccoed soffit also bore on the beam. So in that case, I ran the ceiling joists of the soffit back into the existing structure twice the distance of the overhang. Since the outboard edge of these terminated in a doubled rim joist, I tied that up to the massive ridge beam above with metal strapping. When all was said and done, I don’t think that beam deflected an eighth of an inch!

Overall, the project was a resounding success, although garnering little appreciation from the client (or maybe he just had an odd way of showing it!). At one point, I was informed in less than cordial terms that I must be making too much money, because he thought I was going to hire a bevy of subcontractors to do all the work, like the builder of the original house did – but (shame on me) I ended up doing most the work myself! Ah well, such is the unappreciated lot of the craftsman. I took comfort in the thought that Charles and Henry Greene, whom contemporary records show had plenty of experience dealing with difficult clients, would have understood my frustration.

View Comments

I've been designing houses for over 24 years and must congratulate you for doing what the architect should have done with regard to load conditions.

I've seen this happen a lot. Very few want to get out in the field and get dirty.

And the client didn't appreciate it huh? But boy would they complain if the roof sagged after a couple of years. It's just the nature of our business.

Very nice job.

Thanks GHarmon for the kind words! When some problems arose with a door that the architect spec'd (and which the h.o. didn't like), the h.o. tried to come after me to pay for a replacement. I told him I just ordered and installed what was spec'd, asked why he didn't contact the architect about the problem. He said he didn't want to call the architect, because he charged for phone time! Easier to go after the nice guy on the jobsite, I guess. People are funny.