Letter to the Editor: Financial burdens of complying with future building codes

I subscribe to Fine Homebuilding because my wife and I have a dream of some day building a modest retirement home designed just for us. We appreciate the ideas and insights offered by your publication. However, that dream is fading fast simply due the skyrocketing financial burdens of complying with the current and future building codes. Having read the January 2013 issue, I am compelled to offer my opinion on the articles regarding those codes.

As a professional engineer licensed in multiple states, I am keenly aware of the past difficulties associated with having multiple model building codes applied to various jurisdictions. While those difficulties declined after the introduction of the IBC, new difficulties have arisen and seem to be compounding. One just needs to look at the growing size of each triennial IBC code to have an understanding of the latest problem…death by minutia. The mantra that seems to be guiding current code officials appears to be, “more is better”. If we can conceive of a particular issue, we must write a very precise set of rules to control that issue whether or not those rules are practical and whether or not the issue is of real consequence. Of course, the new rules are always justified by the belief that they are being created for the common good. Those rules are often promulgated by code officials who do not have to make a living working within the boundaries of these codes.

The article “Code Shock” (page 64) indicates that the 2015 ICC will likely require the installation of automatic lighting controls in single family residences. My wife and I are smart enough to turn off our lights when not in use. We are also intelligent enough not to carry a cup of hot coffee between our legs while driving. In either case, we realize the consequences of our own decision-making and don’t require the intervention of others. To force us to install automatic lighting controls will only add considerable cost to our construction with no added benefit. While a standard SPST light switch can be purchased for less than $1.50 at any home improvement store, the cost of the sensor switch is more than $20.00; an increase of more than 13 fold. The cost of installing the two switches may be the same. However, this cannot be said for myriad energy code requirements that involve special design knowledge, sophisticated equipment, unique installation skills, third-party testing and added inspections, not to mention the cost of future maintenance and replacement. Consider that the automated control switch requires more energy and more materials to manufacture versus a very simple SPST switch and the entire logic of that proposed 2015 ICC requirement becomes highly suspect.

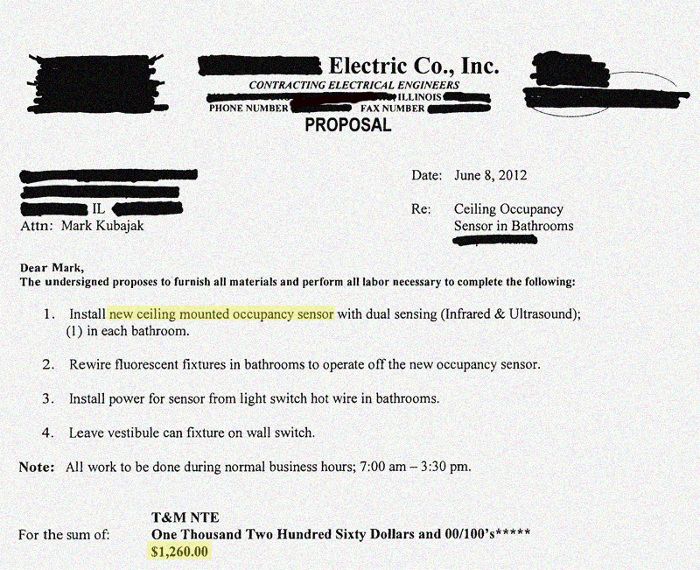

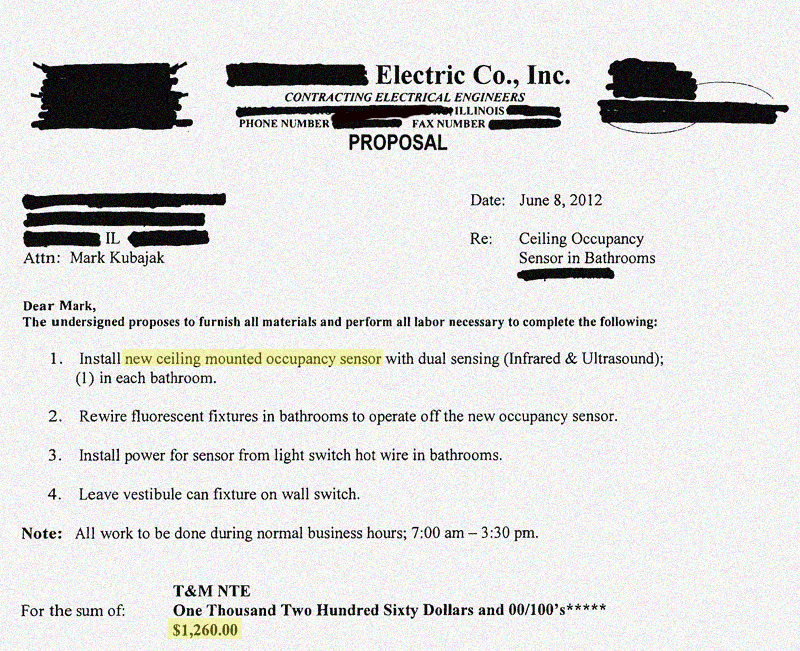

As a further example, attached is a recent quote from an electrician to retrofit automated lighting controls, including motion sensors, into two existing toilet rooms in an existing office building. With a potential cost in excess of $1,200, there will be no economic payback, yet this installation could conceivably be mandated under a not-too-distant code.

I recently watched an interview of an advisor to the State of Illinois who, while touting the benefits of enacting the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) 2012, claimed that it would add only $800 to $1,400 to the cost of a new home in Illinois.1 No reasonable person could believe these figures given all of the cost implications the new energy codes. For justification, just look at the supplementary mechanical systems (translates to considerable added cost) necessary for a kitchen exhaust hood in “How to Provide Makeup Air for Range Hoods” (page 53).

Furthermore, one must also consider the larger economic and ecological impact of requirements enacted in the name of energy savings. Many of the components required to comply with the new codes (lighting switches are a good example) are manufactured in countries halfway around the world in plants with little to no regard for energy conservation. Moreover, the energy to manufacture those products is produced by power plants with little to no pollution controls.

Within the article “Build Like This” (page 40), it was described that the windows were purchased from Germany at a (uninstalled) cost of roughly $845 per unit, plus shipping. While these windows may be superbly efficient, one must ask whether the retired homeowners will ever recover the added cost of super-efficient units through an offset in energy costs. If energy savings (rather than cost savings) is the true goal, then please reveal the energy expended in transporting the windows all the way from Germany.

Had the homeowners chosen efficient, domestically produced, double-glazed windows at say $400 each (no added shipping costs), they may have realized a savings of over $9000 (assuming $2,000 in shipping from Germany). If the German-made windows account for an average energy savings of $300 per year (unlikely for the 1,000 square foot home), then the payback period is 30 years. With lower actual annual energy savings, higher shipping costs, and greater installation costs attributable the heavier triple-glazed and unfamiliar units, the payback could easily be 40 to 50 years! By 30 years, the windows will have likely been replaced anyway. What additional cost in time, money and energy will be spent by the homeowners should they ever need a service part for these foreign units in the future? If all of the aspects were fully considered, it’s likely that the homeowners may have chosen to save the money up front, lessen the impact on the environment by purchasing domestically and employ their fellow American.

In the “Code Shock” article, Mr. Larry Brown makes several valid points. In particular is his concern that many older homes are tremendously energy inefficient. Does it make sense to force the owners of new homes to spend considerably more money for a marginal increase in energy savings when more than 80,000 thousand, uninsulated “Bungalows” constructed between 1910 and 1940 line miles of Chicago streets.2 What about the number of “McMansions” that were constructed in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Think of the energy wasted in simply heating and cooling those oversized spaces.

One need only look at the IECC 2012 to realize that the recent “green plague” also significantly impacts commercial buildings. As written, that code may delay the occupancy of all buildings with more than 40 tons of cooling capacity by up to one year!3 This is due to the requirement that the building be “commissioned” before occupancy is granted. In some climates, to complete the commissioning, it may require that testing be performed nearly a year after the building is ready for occupancy. Imagine explaining to a building owner that, although their building is complete, it cannot be occupied until the jurisdictional requirements are met, and the testing for that cannot take place until next heating season. Additional time and monetary penalties can be incurred subsequent to the required testing should adjustments to and retesting of the building systems be required to pass inspection.

How long can it be before the energy codes start to dictate the maximum square footage of each new house based solely upon anticipated occupancy? After all, if it is truly about saving energy, can’t we save considerably more energy by NOT building unneeded space (compared to a totally unnecessary automated light switch in a closet)? Should future codes be written to ban clothes dryers and dictate the use of clothes lines so that we can save real amounts of energy?

Believe me that I am not trying to even remotely suggest that anyone start dictating what Americans are allowed to do with their own capital, but that is precisely what energy codes are doing. I am simply trying to make a point that common sense and logic seem to disappear when well-intentioned altruisms are allowed to become unsubstantiated societal movements. It reminds me of that long-ago tale of an emperor and his lack of clothing. My solution? Simple. Building codes address public safety and energy codes become unenforceable guidelines. I believe that most people, after considering ALL of the true costs and benefits, would not be so eager to jump on the green bandwagon.

- Chicago Tonight (January 17, 2013) http://chicagotonight.wttw.com/2013/01/17/illinois-new-energy-code

- Historic Chicago Bungalow Association http://www.chicagobungalow.org/about-us/what-is-a-chicago-bungalow

- International Energy Conservation Code 2012, Section 408.2.

Mark J. Kubajak, S.E., P.E.

Fine Homebuilding Recommended Products

Fine Homebuilding receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Affordable IR Camera

Handy Heat Gun

Reliable Crimp Connectors

Little things can add up with new energy-efficiency requirements in building codes

View Comments

Thanks for the well-written letter and feedback on Fine Homebuilding. With regard to your estimate for new motion-sensing switches, perhaps I'm missing something, but I found a motion sensing switch for $51, admittedly much more than a traditional snap switch, but nowhere near $1200.

Wounldn't this work in the application described without any rewiring?

http://www.amazon.com/Leviton-ODS10-ID-Decora-277-Volt-Occupancy/dp/B0007N72P6

As another P.E., I'll certainly agree that there are elements of "over reach" in the developing IBC. But it isn't as if there isn't some pushback on the Code - especially at the local and state level.

I'd also like to note that my opinion regarding those German windows was initially somewhat the same - why spend $800 a window and import them to boot. But if you look into those windows in more detail, you'd find that they are expected to last more than 50 years. And the European Codes (and history) emphasize the construction of homes designed to last a hundred years or more.

You would be hard pressed to find development after development after develop of "McMansions" anywhere in Europe. And the idea that you'd build a home in Europe that was likely to be torn down or extensively remodeled in 20 or 30 thirty years is a stretch too.

Though I'm a proponent of energy efficient homes, I don't think mandating efficiency through the building code is the best way to go. I also don't think sprinkler requirements should be in the building code. And I don't like the 7 3/4 in. rise / 10 in. run stair geometry.

I live in a state that adopts a statewide building code. The state building commission reviews each model code revision and amends out sections they feel suit our state and amends in other provisions. Though the ICC develops codes, it still comes down to state, county or local control through the adoption process. And hopefully there, area residents will let their voice be heard.

Interested people can propose changes to the I-codes during their development each cycle. The 2015 codes are in development now. Lots of new proposals are out there. A few days ago I was reading the proposed changes to just the sections related to decks - about 25 pages. All the proposals are available to see through http://www.iccsafe.org. You can send in written comments and you can attend the hearings to speak as well.

The 2015 energy codes are just a step along a path to net-zero homes. The code development process is influenced by many interests - among them, the DOE. And the projection is within 20 or so years the code will require new homes be built in such a way so they consume no more energy than can be produced on site. This will happen unless people interested in stopping or slowing the process speak up through channels that the code officials will hear.

A thought-provoking letter. Regarding delaying the occupancy of a finished building until the next heating season for commissioning, most building departments will issue a Temporary Certificate of Occupancy.

Mark K writes:

"If we can conceive of a particular issue, we must write a very precise set of rules to control that issue whether or not those rules are practical and whether or not the issue is of real consequence."

It's true that precise rules shouldn't be enforced if another way of achieving the same goal is possible, and grandfathering should apply in all but life-safety issues. Ironically my housemate does prefer the old-style incandescents, and often leaves several on in rooms she's not in.

As for conceiving of issues, it's entirely unclear if the author shares the overwhelming scientific consensus on climate change, and what the implications of it are for future generations. As the consensus understanding of carbon dioxide's long tail means that for every joule of energy we use beyond a sustainable carbon footprint (~ 2.7 tonnes per capita worldwide by the German Advisory Council's budget calculations), around 100,000 joules will be trapped by AGW over many thousands of years. This means the present generation is applying a rather large discount rate to their own protoplasm when they ignore the longevity of the positive radiative forcing involved.

Mark K writes further: "Of course, the new rules are always justified by the belief that they are being created for the common good. Those rules are often promulgated by code officials who do not have to make a living working within the boundaries of these codes."

Very true, and I don't dispute that grandfathering advancing wiring into an existing dwelling sounds over the top, but it also begs the question, "How is leaving your dog or child in a car at the mall to roast very different than doing the same to future generations by ignoring the scientific consensus on a climate change? Cars, planet and houses are all greenhouses upon which you can do heat load calculations, and predict the health of occupants.

As an engineer, what odds do you give future generations to survive heatwaves of unprecedented frequency and duration? Here in Toronto they are predicted to increase fourfold by the 2040's, and that's just another 30 years of having the 800 TW heatgun of unnatural AGW net radiative forcing pointed at the Earth, drying out the breadbasket & fruitbelts in your own country.

The trend with almost all regulations, including the building code is to use it for social engineering. While making a home energy efficient may be desirable, it should not be required by code.

Any building code should be limited to requiring only those things that provide for structural integrity and safety. Anything else might be appended as 'best practices' that are not required.

Automatic lighting would fall in the best practices section. I would expect it to say something like 'recommended but not required and if you do it, these are the requirements.' To be honest, I don't think any code is required for automatic lighting other than what's already there for safe electrical wiring.

Regulations like this are always in danger of being misused for political purposes and pressure must be applied to keep them limited.

I largely agree with the letter's observations about over-the-top regulation. The total costs of many so-called improvements are often not considered and can exceed the potential savings. While there is probably good in working toward net-zero (or better) buildings, the pace should be bound by reality.

My personal view is that there is much efficiency potential in smart upgrading of existing buildings, and that partial government subsidy with minimal red tape should be used to encourage it.

The issue of climate change is still unfolding. Past climate research shows that the northern hemisphere has been mostly covered by glaciers and that our civilization has developed during the latest period of warming. Such warm periods in the past have tended to last only about ten thousand years (putting us at the tail end of this one), with the switch to a hundred thousand years of cold and glaciers occurring in some cases in less than a lifetime. Just as we should be skeptical about over-regulation of building design, we would be wise to recognize the dangers of the current politicization of the climate debate. We need rational scientific and engineering research into the earth's environment and climate cycles with the long term goal of being able to avoid its extremes, both hot and cold.

Timbervalley, there is no dearth of climate science or observations of large effects from AGW. There is plenty of lay opinion on either side, but very little scientific opinion disputing the consensus. If you needed internal surgery, would you sooner go to a qualified surgeon or a General Practitioner, or a barber?

Climate science is already integrated into the engineering and building science design professions, especially for Passive House designers. Engineers Canada are doing adaptation and mitigation work already. http://www.pievc.ca/e/Appendix_D_Final_report_Canada_wide_assessment_sampling_strategy.pdf

Your own Admiral Samuel J. Locklear III recently pointed out that climate change is a threat to international security, both from the effect of thermal pollution, and from conflict over the oil. http://thinkprogress.org/climate/2013/03/11/1700271/pacific-forces-climate-change-biggest-threat-to-regions-security/

I too wish that new problems didn't complicate life any further, but think it's better critique code changes in a more nuanced fashion than to make up a false opposition between the natural and engineering sciences.

The author writes, "Those rules are often promulgated by code officials who do not have to make a living working within the boundaries of these codes."

I'll add to that further with my observation that as building systems of all kinds become more complex, the skilled labor required to properly install these systems becomes more difficult to find at a competitive price. I think this is more problematic at the residential level of design and construction where sub-contractors are hired based on price alone in many cases. Also the labor used to construct most houses tends to be transient, of unknown skills in the unlicensed trades, have language barriers, and may have inadequate educations to understand written and verbal instructions.

Then there are the local amendments to the code to satisfy specific environmental factors (e.g. seismic, hurricane) that make sense to do; but still add a layer of complexity that needs to be addressed. The worst situation is when local authorities amend the code as a revenue generating tool.

Furthermore, the language of the code books tends to be overly complex, allowing for misinterpretations by the trades and inspectors alike. The language should be clear and concise so that it can be understood by all without the need of "code cheater" books to cut to the chase for an answer. This code book language obfuscation reminds me of doctors, lawyers, and other professions who cling to certain archaic practices to keep their professions shrouded in mystery, because it's always been done this way, and other similar reasons.

Section 408.2.4 plainly states that final mechanical inspection is contingent only upon the owner's receipt of the preliminary commissioning report. Likewise, the section plainly states that some tests can be deferred until the climate is appropriate. Ergo, the whole point about people being locked out of their completed buildings while they wait for the seasons to change is just plain wrong.

As the letter writer infers with "buildings with more than 40 tons of cooling capacity" the code requirement has a threshold of 480,000 Btu/h of cooling capacity below which commissioning isn't required at all. Rules of thumb don't work well with commercial cooling calculations but, for the sake of argument, let's say that 40 tons @ 400sf/ton = 16,000sf. So, we're going to build a 16,000sf building -which is easily a $1,000,000 project- but it's too much trouble to pay a commissioning agent to make sure the systems work as intended? Sorry, that is the very definition of penny wise, pound foolish.

These days I recommned basic commissioning for all new construction as a matter of course. I started out with it just on LEED projects about 5 years ago. After seeing the CxA uncover egregious errors by mechanical contractors on every project, errors that would cost the owner money and untold maintenance headaches, I became a believer.

Safety was not always important. In the early 20th century, 77 men died in building Grand Coulee Dam. Accidents were considered a hazard of living. These days, we accept safety as important - the author states in his final paragraph, "... building codes [should] address public safety...".

Likewise, energy use was not considered important. But that is changing as well. Many people, myself included, welcome the new codes and look forward to more efficient buildings.

I also hope that we become smarter and more efficient in our pursuit of energy efficiency. And that includes building codes, as well as design, equipment, and construction.

There is a movie coming out called "Still Mine". It might be cathartic.

The official plot synopsis:

Follows fiercely independent farmer Craig Morrison (Academy Award® nominee James Cromwell), who comes up against the system when he sets out to build a more suitable house on their 2,000 acre farm for his wife (Academy Award® nominee Geneviève Bujold), whose health is starting to fade. Although Craig Morrison is using the same methods his father, a shipbuilder, taught him, times have changed. Craig quickly gets on the wrong side of an overzealous building inspector, who finds just about everything unacceptable, including the unstamped wood Craig has milled from his own trees. As Irene becomes increasingly ill – and amidst a series of stop-work orders – Craig races to finish the house. Hauled into court and facing jail, Craig takes a final stance against the system for individual freedom and independence.