Drilling Deep

Fracking a water well is a pretty benign process -- and without it we'd have an unbuildable lot.

The bedrock in the area where we are building the FHB House is pretty close to the surface. It’s mostly granite without many cracks to hold water, so I expected some challenges finding water. The well driller came in mid-April. Hoping to see good news emerge from the ground, I stood by as he worked. The ghostly light gray color of the cuttings emerging with the drill-water was not a good sign. By the end of the first day the driller was down almost 300 ft. without anything. The next day, he called me mid-morning to report he was dry at 500 ft. Bad news.

The bedrock in the area where we are building the FHB House is pretty close to the surface. It’s mostly granite without many cracks to hold water, so I expected some challenges finding water. The well driller came in mid-April. Hoping to see good news emerge from the ground, I stood by as he worked. The ghostly light gray color of the cuttings emerging with the drill-water was not a good sign. By the end of the first day the driller was down almost 300 ft. without anything. The next day, he called me mid-morning to report he was dry at 500 ft. Bad news.

Without a productive well, the lot would essentially be unbuildable. For lots in new developments in town, there is a requirement that the land developer drill a well on each prospective lot before the development is approved. Since this is an in-fill lot that was subdivided over 50 years ago, a well wasn’t required for a building permit — only for a C.O.

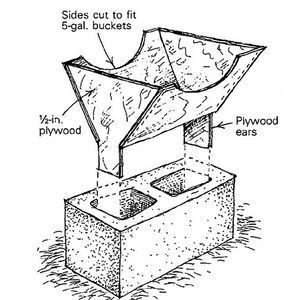

So, the next step was hydrofracturing. Fracking isn’t always a dirty word. Here it’s more like a deep cleanse. New wells in the area are regularly fracked. Unlike fracking oil wells, the fluid used is just clean, fresh water. The high pressure pump drives the water into small fissures in the rock in the hope that it will clear out cuttings that plugged them up during the drilling process.

The process took about four hours, start to finish, and the crew pumped about 1000 gallons of water back into the well.

The process took about four hours, start to finish, and the crew pumped about 1000 gallons of water back into the well.

After a few days they checked the well production. The result was 1 gallon/minute. That might not sound like a lot, but at 500 ft. deep the well itself provides a pretty big reservoir. With low-flow fixtures and no lawn sprinklers, the output should be plenty.