Enhance Style with the Right Entry Door

As the focal point of the house, it's important for the entry door to be appropriate to the house style.

Synopsis: Architect Lynn Hopkins provides examples of doors that are appropriate to each of four broad styles: colonial, Victorian, bungalow, and modern. She considers factors such as sticking, windows, decorative elements, and muntin patterns.

When it comes to selecting a door for your house, it’s best to stay true to the house’s established style. For purposes of door selection, architectural styles can be lumped into four broad categories: colonial, Victorian, bungalow, and modern. The drawings on the following pages show some examples of doors that are appropriate to each of these styles.

Material choices play a role in how well a door fits a particular style. For example, if your house calls for a panel door, wood rail-and-stile construction with its sharp profiles looks best. Some panel doors of fiberglass and steel can have shallow panels with mushy corners that look artificial, so look at as many door samples as you can before purchasing.

All entry doors are not created equal, so do the research. (For more on doors, see “Choose a Quality Entry Door”.) The best entry doors use advanced materials and construction methods to stay looking good for years to come.

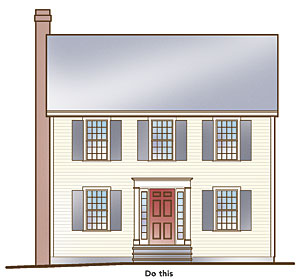

The door should fit the facade

As the focal point of the house, it’s important for the entry door to be appropriate to the house style. In the upper drawing, the muntins in the sidelites are proportional to the 12-over-12 windows, and the solid, windowless six-panel door is in keeping with the relatively austere colonial facade and open, exposed nature of the entry. The Craftsman-style door in the lower drawing, however, is out of place on this colonial. The door window is too large for entry without a porch to serve as a buffer, and the size and shape of the muntin pattern and door panel are at odds with the size and style of the windowpanes and door surround.

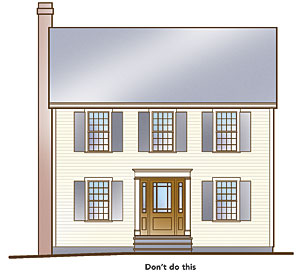

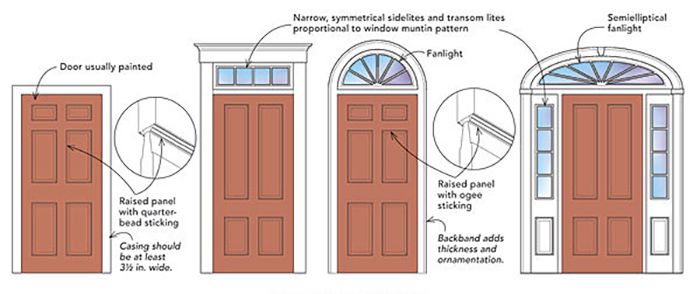

Colonials and Capes: 1700s-Present

Most early colonials and Capes (as well as Georgian- and federal-style houses) had solid-wood doors without glass. To accommodate wood movement, the doors had four or six raised panels. Sticking—the treatment of the rails and stiles at the points where they meet the panel—usually required a simple shape, such as an ogee, quarter-round, or quarter-bead, that could be cut with hand tools.

Doors on colonial-style houses can be combined with a pair of sidelites arranged symmetrically on each side of the door. Above-the-door transoms and fanlights also were stylistically appropriate ways to bring light to the entry hall. They can be rectangular, semicircular, or semielliptical, and can be combined with sidelites. The size of the panes in the transom and sidelites should be proportionate to those of the windows in the rest of the house.

Traditional colonial styles can have a decorative surround consisting of pilasters with an entablature, pediment, or arch. The trim can be flat, vertical boards, with a thicker and/or taller head trim that might sport a cornice cap. Porticoes and similar porchlike additions were not introduced until colonial-revival periods.

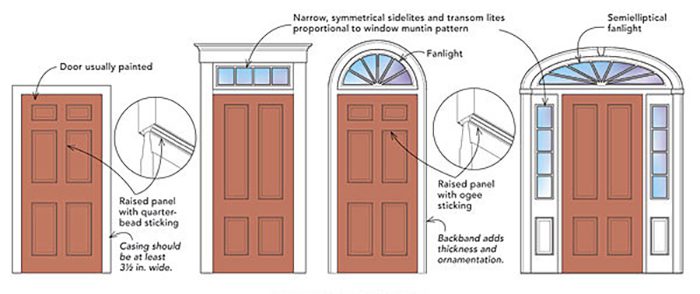

Victorian: 1830s-1900s

The middle of the 19th century witnessed an explosion of industrialization and the advent of a “more is more” aesthetic. Beginning with the comparatively tame Greek revival, the era continued on through a series of romantic styles including Gothic, Italianate, Second Empire, stick, Queen Anne, and shingle. Entry into the house was celebrated with a porch as a transition between public and private space, allowing for glass in the doors without feeling too exposed to the outdoors. Also, ornament appeared not just around the door but over the windows, under the eaves, along the rake boards, and even along the ridgeline of the home. For houses that hark to this era, the focal point of the door is glass, often etched or stained. Instead of a single, solid door with sidelites, these styles favor a pair of doors with glass. The shape of the glass can be an oval or rectangle with an arched top, or it can mimic the windows. Doors should still be rail-and-stile construction with raised panels, but the panel might have a more complicated profile. Period doors often have a projecting bolection molding with an elaborate profile at the juncture between frame and panel.

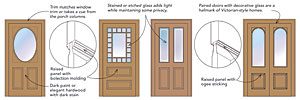

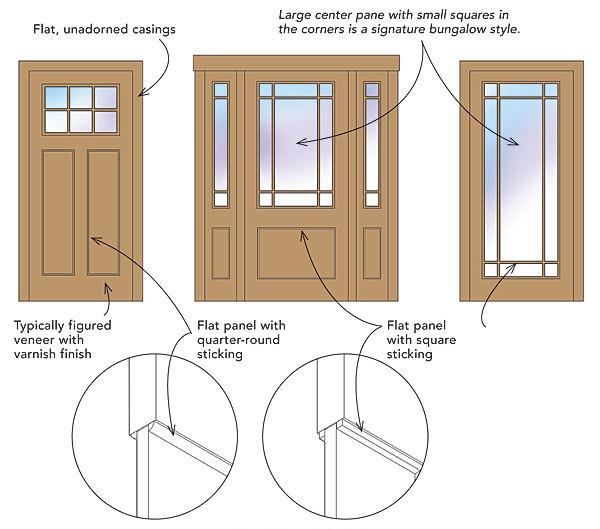

Bungalow: 1900s-1940s

This era, which includes the Craftsman and prairie styles, celebrated unadulterated materials and made an aesthetic of simpler construction methods.

Doors for houses of these styles have rails and stiles, often with flat panels and simple rectangular, quarter-round, or quarter-bead sticking. Often, doors have fewer and/or wider panels than ones for earlier eras.

As with the Victorian home, porches are an important component of this style and make it comfortable to have generous amounts of glass in the doors. Muntin patterns should be simple and rectangular. A popular door introduced at this time had six panes of glass in the upper portion of the door and two large, vertical wood panels below. The upper portion of the door allows the owner to see who is on the stoop, while the solid panels below provide privacy and security. This door takes up less width than a solid door with sidelites, making it particularly useful for small houses with narrow entry halls and in areas where security and privacy are a concern.

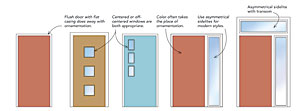

Modern: 1930s-Present

Modernism embraced mass production and manufacturing as an aesthetic with a “less is more” credo.

The flush door exemplified the best and worst of this new style. Visible rails and stiles disappeared, replaced with a slab made of durable but inexpensive materials.

The flush door is most successful on houses with many other modern elements, when it stretches floor to ceiling, or when it is combined with a transom to give the same impression. It is also attractive when combined with an asymmetrical sidelite.

Split levels, raised ranches, and other contemporary suburban styles often straddle two different (and conflicting) eras. Their attached garages place them clearly in the machine age, so a strong argument can be made for pushing these houses further in the modern direction with a flush door.

But if these houses have multipane double-hung windows, shutters, and a pitched roof, a flush door is inappropriate. These traditional elements can be accommodated with a simple rail-and-stile door with just one or two flat panels. The rails and stiles provide a nod to traditional construction, while the large, wide panels are more modern. A door with three, four, or five horizontal flat panels also can be appropriate because it acknowledges the horizontality of the building form. Avoid fancy raised panels, applied molding, ornate sticking, and overly decorative windows, and use trim that matches the windows.

Drawings: Lynn Hopkins